STORY HIGHLIGHTS

Augmented reality for public safety →

Hillsborough PD collaboration →

Cybersickness and the VR experience →

Student-run research →

Virtually there: Black history →

» INTERACTIVE REALITIES LAB ADVANCES NEXT-GEN TECH

As flames rapidly engulf a burning building, the heat becomes overpowering. Thick, choking smoke rises quickly. Firefighters drop to the ground and crawl beneath the haze. They are looking for victims but can barely see the hands in front of their faces.

Now imagine if they could wear specialized glasses that could “see through” the smoke – illuminating each room’s floor plan, identifying victims’ locations, and pointing out where fellow first responders are in the building.

This is augmented reality, or AR. Dr. Regis Kopper believes AR will transform many aspects of public safety within the next 10 to 20 years.

While this and similar next generation tools are not fully developed yet, the assistant professor and his computer science students are working with police, firefighters, and EMTs right now to design the interfaces that these technologies will require.

Funded by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, the projects use virtual reality – VR – to simulate future AR technologies, with a goal of determining what types of interfaces will work best for the end users.

With tech like this, EMTs of the future could glance at an armband they’re wearing and “see” a patient’s real-time vital signs pop up on a virtual computer screen that appears almost in thin air. By simply pointing at the virtual screen, the EMT could toggle from a patient’s vital signs to other relevant information such as medical history, prescription information, and allergies.

Kopper and his Interactive Realities Lab team gather information through interviews and ride-alongs to develop the simulations. This allows first responders to provide critical input in the design of future systems. “It’s always important to have the end user be a part of the design, and in public safety, not doing so could be particularly dangerous,” Kopper says. “There is risk involved in public safety operations, and we want users to be able to operate and trust these systems.”

When it comes to law enforcement, VR will be used both to simulate upcoming technologies and to improve current training protocols. Kopper and his team are currently launching a project with the Hillsborough Police Department to test their tech – while also helping officers learn to handle or avoid potential escalations in routine traffic stops.

Instructors will be able to tweak each scenario to include different types of cars, circumstances, and driver demographics such as race and gender. “One of the great benefits of VR is that you can repeat a scenario as many times as you need and control very precisely what you want in the simulation,” Kopper says. “It will offer the ability to debrief, discuss, and even replay the scenario.”

Next-gen tech will eventually take this work a step further. Police officers of the future could glance at a license plate through AR glasses – or even contact lenses – and immediately access relevant information such as the car’s ownership, a driver’s criminal history, or other potential risks.

“The hypothesis is that officers could more immediately make decisions based on real-time evidence rather than potential bias or profiling,” Kopper notes. And, by not having to turn their backs and return to their patrol cars to access critical information, officer safety would be enhanced as well.

The researchers are sharing the data from the public safety project, so that others can access the findings. “Our goal for this project specifically is not to make profit, but to make impact,” Kopper says.

» This year UNCG launches a PhD in computer science. Dr. Kopper’s interdisciplinary research projects offer incoming students an unusual experience: “A lot of times in our field, we are confined to our labs and implications of the work we do are not immediately visible. It’s nice to be able to see the effect and the potential.”

» This year UNCG launches a PhD in computer science. Dr. Kopper’s interdisciplinary research projects offer incoming students an unusual experience: “A lot of times in our field, we are confined to our labs and implications of the work we do are not immediately visible. It’s nice to be able to see the effect and the potential.”

Kopper with undergraduate researcher Kadir Lofca

» user experience

As the saying goes: You only have one chance to make a first impression.

Kopper’s lab members keep that in mind as they work toward streamlining users’ experience with virtual reality.

“VR technology has the potential for so many important and useful applications, but if you have a bad experience with it the first time, you will become a skeptic,” says Kopper. “It’s difficult to go back and want to give it another try.”

One of the pitfalls of VR is that it can cause “cybersickness.” Feelings of nausea or motion sickness can arise when a user’s eyes tell the brain they are in motion, but signals from the rest of the body disagree.

To combat this, Kopper and his Duke University PhD student Zekun Cao theorize that adding small static elements will lessen viewer discomfort. For instance, if viewers sense they are inside a stationary cockpit while “flying” in VR, that might help with feelings of stability. Or perhaps even less obtrusive elements could help, such as tiny dots that don’t move in the user’s peripheral vision.

“We are running studies on this right now,” Kopper says, “and we are getting some promising results.”

The lab is also interested in how well virtual reality training translates to real life learning.

Think of it this way: When you bowl in a Wii video game, you are holding a controller, but not an actual bowling ball. It makes for a fun and entertaining game, but without the weight of the ball, you won’t learn accurate techniques for how to bowl in real life.

Currently, Kopper and UNCG undergraduate Kadir Lofca are looking at how users in VR training perceive the passage of time. “In virtual reality, time passes differently,” Lofca says.

Here too, the weight of the controller may matter.

For example, firefighters must hold a Hazmat gauge up to an air vent for 30 seconds to measure the level of poisonous gas being emitted. In a virtual reality setting, researchers need to know whether mimicking the weight of an actual Hazmat gauge versus using a regular lightweight VR controller impacts how firefighters estimate the 30 seconds.

Measurements like these are vital.

“When we’re talking about training firefighters, police, and first responders,” says Lofca, “it has to be accurate.”

» Rebuilding History

Books, documentaries, and museum exhibits offer us peeks into history, but what if you could actually walk back in time?

While most of the Interactive Realities Lab’s projects look to the future, a few look back, shining a light on lost history.

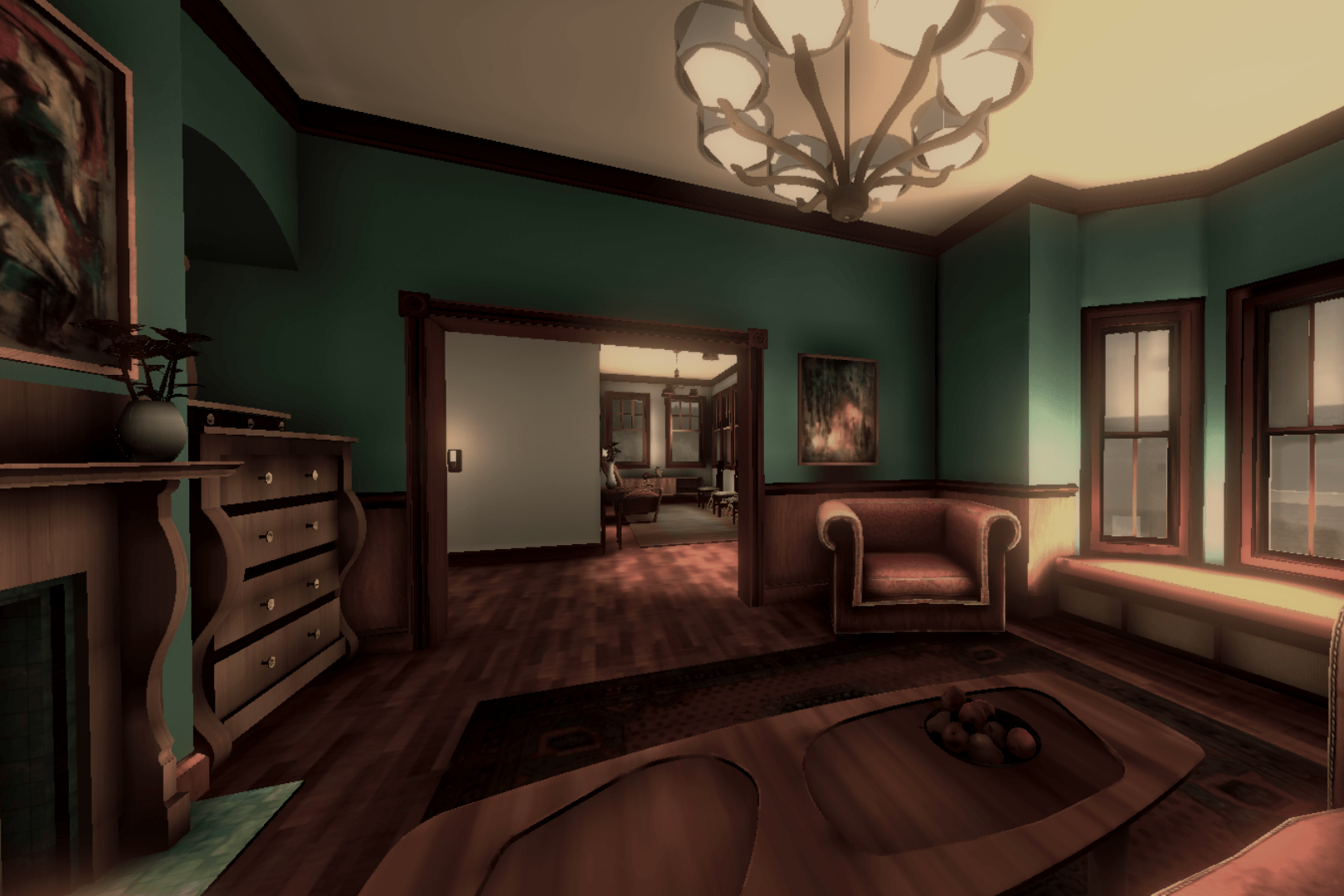

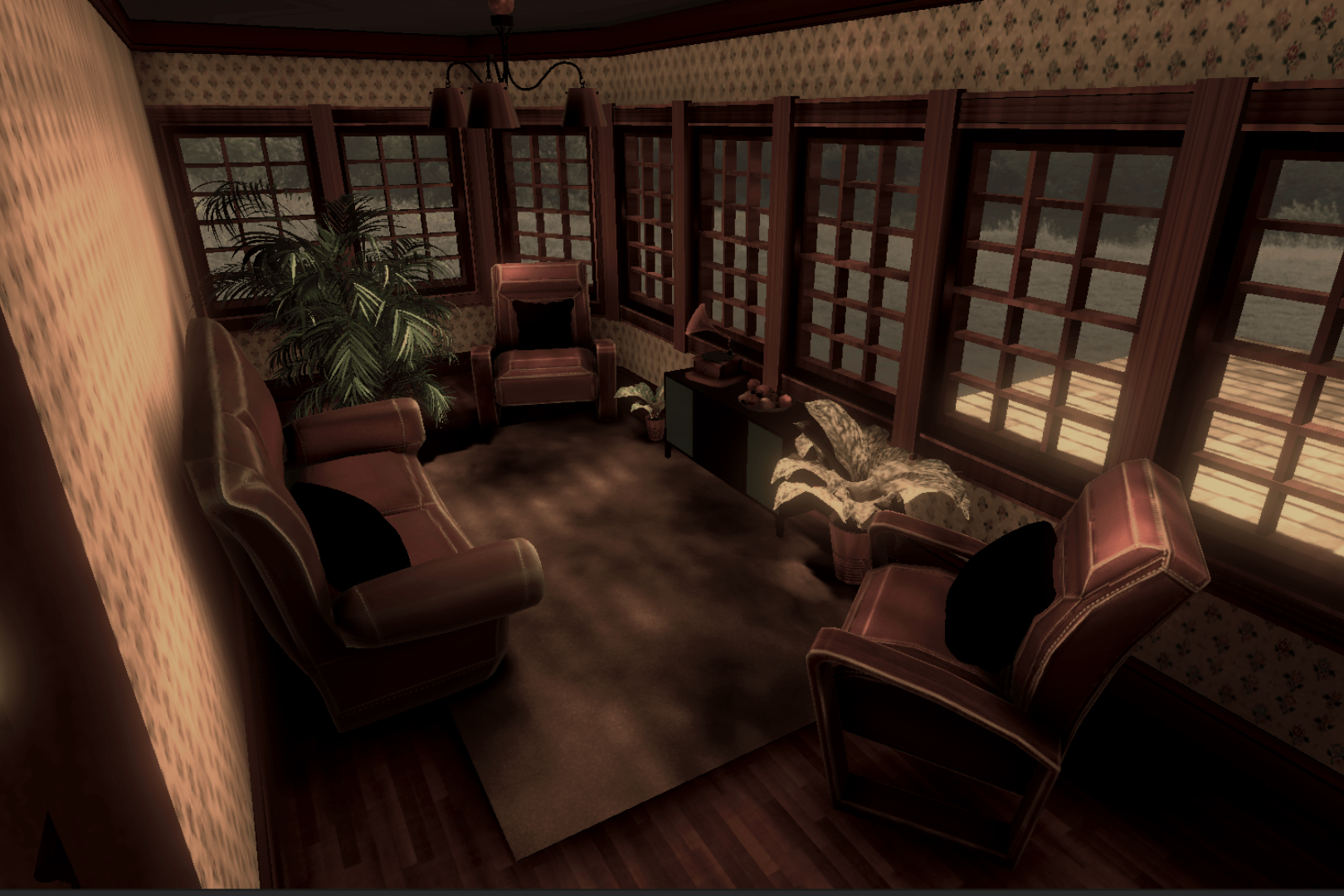

Last year, undergraduate Kadir Lofca created a virtual walk-through of Greensboro’s Magnolia House. The former “Green Book” hotel provided lodging known to be safe for African American travelers during the Jim Crow era.

The work was conducted in partnership with Dr. Asha Kutty and UNCG’s Interior Architecture Department, and the immersive experience is based on the designs of undergraduate Hannah Tripp. Now, viewers can “walk” through the hotel as it would have looked decades ago.

“Every single detail adds up to create the overall experience,” says Lofca, who used VR to showcase period furnishings, color schemes, and even specialized sound effects such as birdsong outside the house and music that grows stronger as viewers approach an upstairs bedroom where a victrola is playing.

» Magnolia House site manager Melissa Knapp tours the historic hotel in virtual reality, alongside the UNCG team that designed the experience.

“School children who participated in the experience said they felt as if they had been transported to a different place and time,” Kopper says.

That is also one of the goals of a two-year project funded through the National Archives to virtually reconstruct two African American neighborhoods destroyed decades ago in Charlotte’s urban renewal. Viewers will be able to “walk” throughout the Brooklyn and Greenville neighborhoods, where residents were displaced by the thousands during the 1960s and 70s.

The project team includes principal investigators from Johnson C. Smith University and researchers from UNC Charlotte. Kopper’s lab and Duke University’s Office of Information Technology and Digital Humanities Lab are building the interactive experience, which can be navigated with a keyboard and mouse or a VR headset.

Viewers will even be able to “enter” some of the buildings, where every detail is grounded in historical records, photographs, interviews with residents, city documents, and audio recordings.

It’s a powerful way to visualize once-vibrant Black communities – and see how they were devastated by systemic racism and segregation.

“Virtual reality can help us experience history from a first-person perspective,” Kopper says. “It gives people a unique experience and can really leave an impression.”