French impressionist Edgar Degas once said, “Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.”

That’s certainly the case at the North Carolina Museum of Art’s newly expanded African art gallery — an effort made possible through the expertise of Elizabeth Perrill, associate professor of art history.

At a time when African art is becoming increasingly popular among collectors and museums worldwide, Dr. Perrill’s skilled oversight as curator helped the museum reimagine and nearly triple the size of this gallery space. In particular, Perrill brings a specialized expertise in Zulu ceramics, with her seminal book on Zulu pottery now a touchstone for educators, curators, and anyone developing collections in the United States, Europe, and South Africa.

Her contribution also comes as a timely addition to the state museum during an era when African immigration to the southeastern United States, including North Carolina, is at an all-time high. The state’s African-born population has doubled each decade since the 1970s. As of 2014, nearly 6 percent of the state’s foreign-born residents came from Africa.

“As we become a destination state for African immigrants, we want all of North Carolina to understand the diversity of Africa,” Perrill says. “We want visitors to recognize that Africa is an entire continent, and there are subtleties and complexities within each region.”

Visitors to the gallery, which opened this past summer, are now greeted by a large map of Africa divided into regional sections. The exhibit’s focus areas are dedicated to specific kingdoms, regions, and aesthetic traditions spanning 16 centuries. Section titles such as “Gold as Regalia,” “Art Abounds,” and “Geometry and Abstraction” are designed to “shake people out of their expectations of what African art is,” Perrill says.

More than 100 of the pieces on display — including ceramics, textiles, jewelry, metal works, wooden sculptures, masquerade attire, beadwork, paintings, and multi-media collage — have never been seen before in a public exhibition or have not been exhibited in decades.

One of the most contemporary pieces is a transitory chalk mural by Nigerian-born artist Victor Ekpuk, who now lives in Washington, D.C. During one week’s time, Ekpuk created the 30- by 18-foot mural, titled “Divinity.” Immigrants and refugees from Africa who now live in North Carolina have joined in conversations about the piece, which will remain up for one year. They will be invited to return and help Ekpuk erase the mural next year, in accordance with many African cultural traditions that celebrate art as ephemeral.

Feature photo: Victor Ekpuk’s “Divinity.”

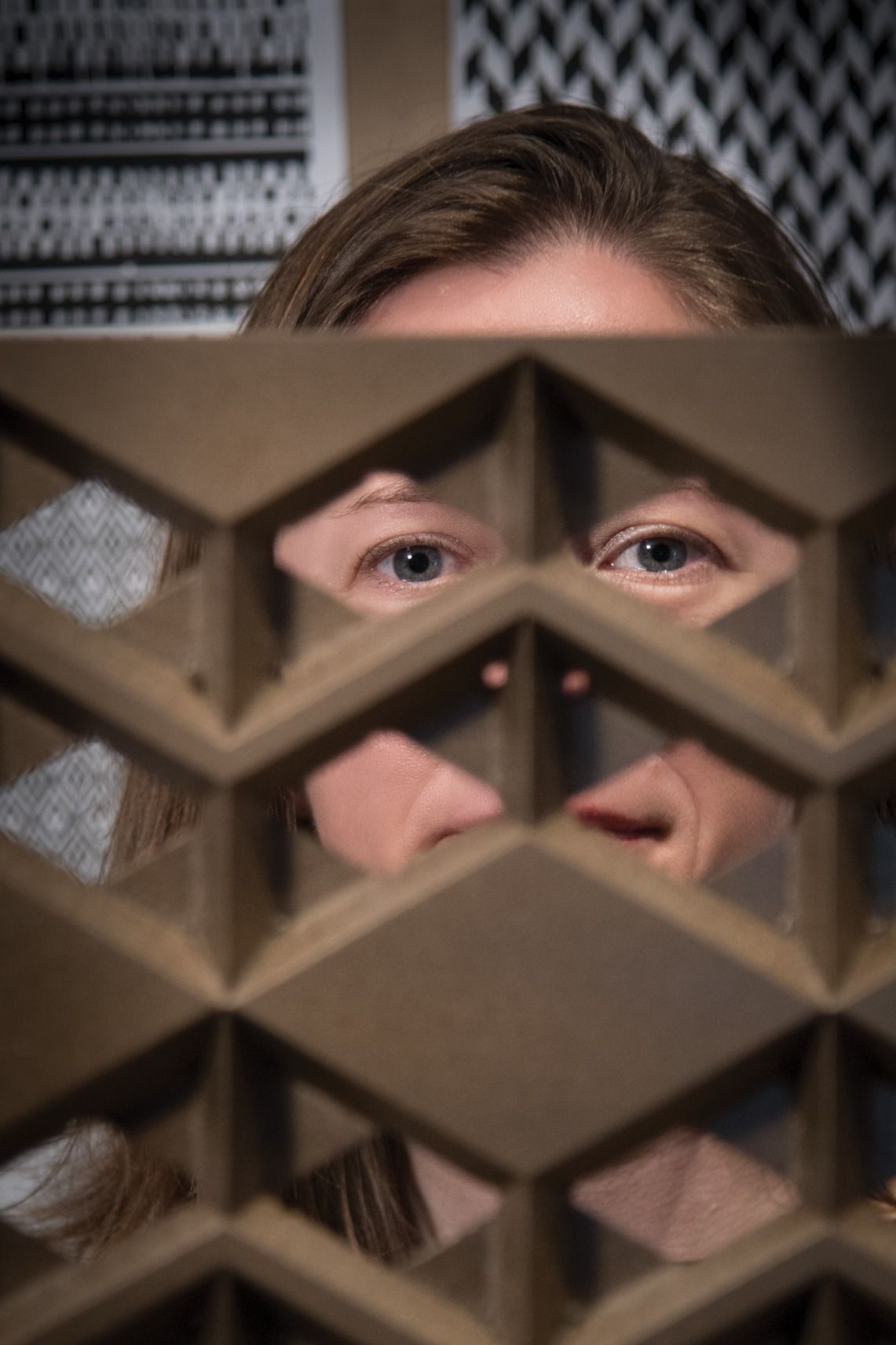

Inset photo above: Perrill, seen through a screen digitally fabricated for the gallery and inspired by the NC Museum of Art and African modernist architecture.

Inset photo below: Burnished earthenware by Zanele Nala, from the collection of Jane and Richard Levy. The Levys’ Zulu collection was inspired by Perrill’s work. “The Nalas are the most famous family of contemporary Zulu ceramists to date,” she says.

The gallery, which was funded through a $500,000 grant from the William R. Kenan Jr. Charitable Trust, also features a North Carolina wall dedicated to the state’s connections to African art. Currently, that display includes a collection from Bennett College — a historically black women’s college in Greensboro — that rivals the quality of objects at the Met, Perrill says.

In addition to studying African art itself, Perrill has become known for her work examining the life histories and cultural identities of Zulu artists — most often women. “Many people look at the aesthetics of art, but I want to know the backstory of exactly what informed the style,” says Perrill, who has spent a decade getting to know artists personally, often staying in their homes.

This firsthand approach to research has given her an unrivaled expertise in the shifting hierarchies of the art marketplace. For instance, because many Zulu ceramic pieces are created for spiritual or utilitarian purposes, they were not considered art until the 1980s and 1990s. Even today, a discrepancy exists between what collectors define as “fine art” versus “folk art.”

“It’s important to me to document the voices of women as artists and connect that to the art market and what it means to make African art,” Perrill says. “Dealers have started to respond to the scholarship and have started to say, ‘Oh we should know the names of the artists because they are alive and working.’” In the book she’s currently working on, tentatively titled “Burnished: Zulu Ceramics, Between Urban and Rural South Africa,” she’s bringing those stories of artists intersecting with the market to the fore.

“I’ve started to realize how much that I’m a part of the market now. I can’t be separated from it as a scholar. As a scholar, you’re constantly making decisions that you realize are impacting people’s lives.”

She hopes her knowledge and experience will deepen viewers’ understanding of the new gallery space as well as impact the future of collecting African art.

“With the museum’s launch of the larger space, donors and funding agencies start to realize that you’re dedicated,” she says. “I really think that the North Carolina Museum of Art has signaled through this reinstallation that we’re committed. All of this is going to strengthen art in North Carolina.”