On a quiet Sunday in March, Dr. Debra Barksdale got her first tour of the NIB – UNCG’s new Nursing and Instructional Building.

As she entered, Barksdale gazed across the wide-open atrium with 15 rows of seats rising from the first floor to the second, and then up the long staircase that stretches from the second floor to the fifth, totaling 100 steps.

At the time, Barksdale was considering an offer to become the next dean of the School of Nursing.

She walked through nearly every room in the 180,000-square-foot building, passing long walls of windows offering panoramic views of campus and the Greensboro skyline. By the end of her tour, she had gotten in a good workout.

“I actually got 6,000 steps in that building,” she says. Barksdale came away impressed, by not just the facility but the faculty and the school’s ambitious plans for the future.

On March 31, she was introduced as the new dean. The appointment follows five years as a nursing professor and associate dean of academic affairs at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Before that, she was the first Black faculty member to achieve the rank of full professor with tenure in UNC Chapel Hill’s School of Nursing.

With a new dean and a new $105 million building, the School of Nursing is poised to expand in every direction, including in terms of its nationally recognized research, which has focused for the past two decades on addressing health disparities in vulnerable populations.

Since last fall, five new research faculty members have joined the school, and Dean Barksdale has no plans to stop there. “Increasing research levels is a goal of the University and the School of Nursing,” Barksdale says. “I plan to work with the school to help increase research productivity and recruit more researchers.”

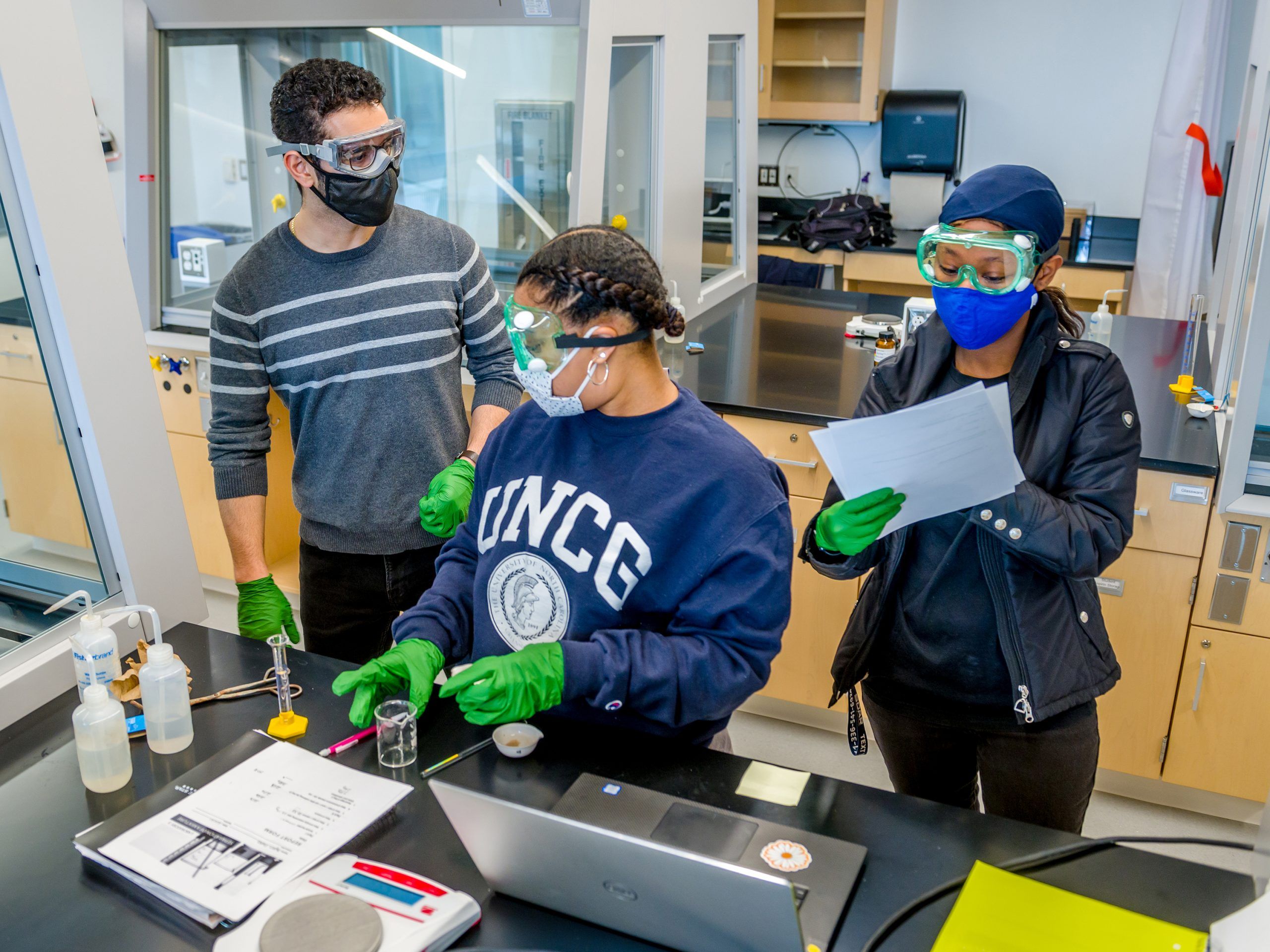

CROSS-DISCIPLINARY BENEFITS The NIB boasts 39 learning labs and 14 classrooms that will be used for nursing education as well as for STEM disciplines across campus. The building also hosts state-of-the-art research labs run by the departments of Biology and Chemistry and Biochemistry. On the first floor, the School of Health and Human Sciences and the School of Nursing share a community engagement center, where research teams can meet comfortably with participants and collaborators.

Increasing research levels is a goal of the University and the School of Nursing.”

– Dean Debra Barksdale

Making Room for Research

When Associate Dean for Academic Programs Heidi Krowchuk joined UNCG’s nursing faculty in 1990, only a few of her colleagues conducted research.

The Moore Building, which opened in 1969 and served as the home of the School of Nursing for 51 years, allocated a small space – now a supply closet and a few classrooms and staff offices – for that work.

As the school’s research efforts grew, research spaces were cobbled together across four different buildings. They didn’t have a wet lab, so faculty members stored their biological samples, such as blood and hair, in other schools’ labs around campus.

As the NIB was designed, administrators in the School of Nursing wanted to ensure that the plans included plenty of space for faculty, staff, and student researchers, plus room to grow.

“That was one of the discussions we had, that we ensure we had ample research space not just for now but also for the next 10-15 years,” says Dr. Debra Wallace, senior associate dean for research and innovation.

The impressive new glass-enclosed facility, which sits next to the oldest building on UNCG’s campus – the 129-year-old Foust Building – reflects those priorities.

Most of the School of Nursing’s space on the second floor is reserved for research, including four large suites where scholars can comfortably meet. Two floors up, there’s a large wet lab with a safety shower, a refrigerator and freezer for storing biological samples, and enough room for five researchers to conduct lab work at the same time.

“Now we have our own space,” says Dr. Krowchuk. “We’ve designed the building thinking futuristically, since we know that we’re going to expand our research and we

needed the space to do it.”

We’ve designed the building thinking futuristically, since we know that we’re going to expand our research and we needed the space to do it.”

– Associate Dean for Academic Programs Heidi Krowchuk

Serving the Underserved

As they launched their PhD program in 2004, nursing faculty decided to focus their research on health disparities in vulnerable populations.

A major initiative within the School of Nursing has been the TRIAD Center of Excellence in Health Disparities, which the National Institutes of Health funded with two grants totaling $11.5 million. Wallace served as principal investigator on the project.

Interdisciplinary teams operating through the center examined self-management of diabetes among Hispanic populations, nutrition and blood pressure control among African American adults, risky sexual behavior among teenage girls, and more.

The grant that launched the TRIAD Center of Excellence in Health Disparities is one of the largest NIH research grants in UNCG’s history.

Faculty from NC A&T, NC Central, and Winston-Salem State as well as local community partners and agencies collaborated on center projects, which were ultimately, says Wallace, “about the impact we can have on our community to improve health.”

The research trajectory chosen by faculty in the early 2000s is no less relevant today.

“We are much more aware of health disparities than we were 30 years ago or 25 years ago or 20 years for that matter – the literature has just really expanded,” says Krowchuk.

“Now everybody is talking about social determinants of health because we know that where you grow up, how you grow up, what kind of neighborhood you lived in, and what access your family had to resources – that really impacts your health down the road.”

The new dean’s own research interest in stress and heart disease among African American adults aligns perfectly with the school’s focus.

Barksdale became interested in the ways stress negatively affects the body after a dentist told her that she had developed temporomandibular joint syndrome, or TMJ, from being stressed as a graduate student at Howard University. She was clenching her teeth at night.

Later, when she was working at a Maryland clinic, she noticed that many of her patients were young Black men who had high blood pressure.

“They weren’t obese and didn’t have other risk factors traditionally associated with high blood pressure, but they frequently indicated that they were under this tremendous stress as Black men,” Barksdale says.

Recent research projects at the School of Nursing

a collaboration with Cone Health examining how hospitals assign work to nurses, with the goal of improving quality of care and safety, led by Dr. Cindy Bacon

weight management interventions for young Black women that address chronic psychosocial stress, negative emotions, and eating behavior patterns, led by Dr. Stephanie Pickett

a study of long-term cardiovascular health risks experienced by women diagnosed with hypertension and other cardiometabolic complications during pregnancy, led by Dr. Forgive Avorgbedor

a school-based therapy program study to help children cope with asthma, conducted by Dr. Colleen McGovern and the University of Rhode Island and Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Ohio

Health disparities are prevalent in our state and in our community, and our faculty are committed to alleviating and trying to remove those disparities.”

– Senior Associate Dean for Research and Innovation Debra Wallace

Who enters nursing?

Complex issues involving race also play a role in the school’s commitment to being an inclusive learning environment.

This year, two teams of nursing faculty have won large U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration grants that will support their work to recruit, prepare, and retain nursing students from underrepresented backgrounds, to diversify the nursing workforce. A four-year $2.2 million effort led by Dr. Audrey Snyder will focus on gerontological nurse practitioners working in underserved primary care settings. A five-year $770,511 effort led by Dr. Carrie Hill will focus on maternal child health.

Dr. Pamela Johnson Rowsey’s interest in nursing student diversity sparked over a decade ago, at a graduation event she attended at another institution.

“Normally the faculty would be on the floor, but that year we were all sitting on the stage,” Johnson Rowsey says. From that vantage point, she was forcefully reminded of how few nursing students were students of color. “I’ll never forget this. I thought to myself, ‘What can we do to improve this?’”

As Dr. Ernest Grant – president of the American Nurses Association and the first Black male to earn a nursing doctorate at UNCG – states in a 2019 op-ed in Modern Healthcare, “a diverse nursing workforce helps to increase access to quality healthcare services, address preventable health conditions, and tackle social determinants of health” because it “fosters cultural competence and removes sociocultural barriers to care in clinical settings.”

But in 2020, the National Nursing Workforce Survey found that only 6.7% of registered nurses in the U.S. identified as Black/African American and only 5.6% identified as Hispanic/Latinx.

Johnson Rowsey, now chair of UNCG’s Adult Health Nursing Department, co-authored an article about increasing diversity in the workforce in the Journal of Professional Nursing last year.

If we want to see a change, she says, “We’ve got to go out and start recruiting at middle school and high school levels. Actually, high school might be too late.”

In focus groups she and her collaborators conducted, nursing students also spoke about the need to correct myths and stereotypes about nursing, in terms of what the job entails and who becomes a nurse. Media portrayals, both positive and negative, are a major contributor to perceptions of nursing.

Dr. Ernest Grant, president of the American Nurses Association and the first Black male to earn a nursing doctorate at UNCG, attends the NIB ribbon cutting with Dean Barksdale

We’ve got to go out and start recruiting at middle school and high school levels. Actually, high school might be too late.”

– Department Chair Pamela Johnson Rowsey

Barksdale decided to become a nurse as a kid growing up in rural Virginia when she watched the TV sitcom “Julia.”

The show is often credited as the first weekly TV series to star an African American woman in a non-stereotypical role, with the title character played by Diahann Carroll working as a nurse.

In 1967, one year before “Julia” premiered on NBC, Dr. Ernestine Small became UNCG’s first minority faculty member when she joined the School of Nursing.

Now in 2021, Barksdale, the daughter of a sharecropper, has been hired to lead the School of Nursing into the future.

“It’s important for students to have faculty that look like them who understand their experiences,” Barksdale says. “This gives them hope and encouragement that they too can reach their goals and potential.”

The impact won’t end there, Johnson Rowsey adds. “Barksdale’s hiring sends a message for faculty as well that the University is committed to having diverse students, faculty, and staff.”

It’s a new chapter, in a new building, at the UNCG School of Nursing.