Growing Evidence

In a UNCG study on the psychological, biological, and social factors linked to rapid infant weight gain, researchers followed 299 women and their infants from pregnancy to toddlerhood and found that infant feeding practices associated with obesity, known as obesogenic practices, play a central role.

Examples of obesogenic practices described in the UNCG iGrow study’s recent Pediatric Obesity paper include watching television while feeding a baby, formula feeding, and supplementing a bottle with additional foods.

“The key take home point is that what and how parents feed their infants in the first 6 months of life has tremendous implications for obesity risk, and childbearing parents who experience more stress during the prenatal period are particularly likely to engage in these unhealthy practices,” says Dr. Esther Leerkes.

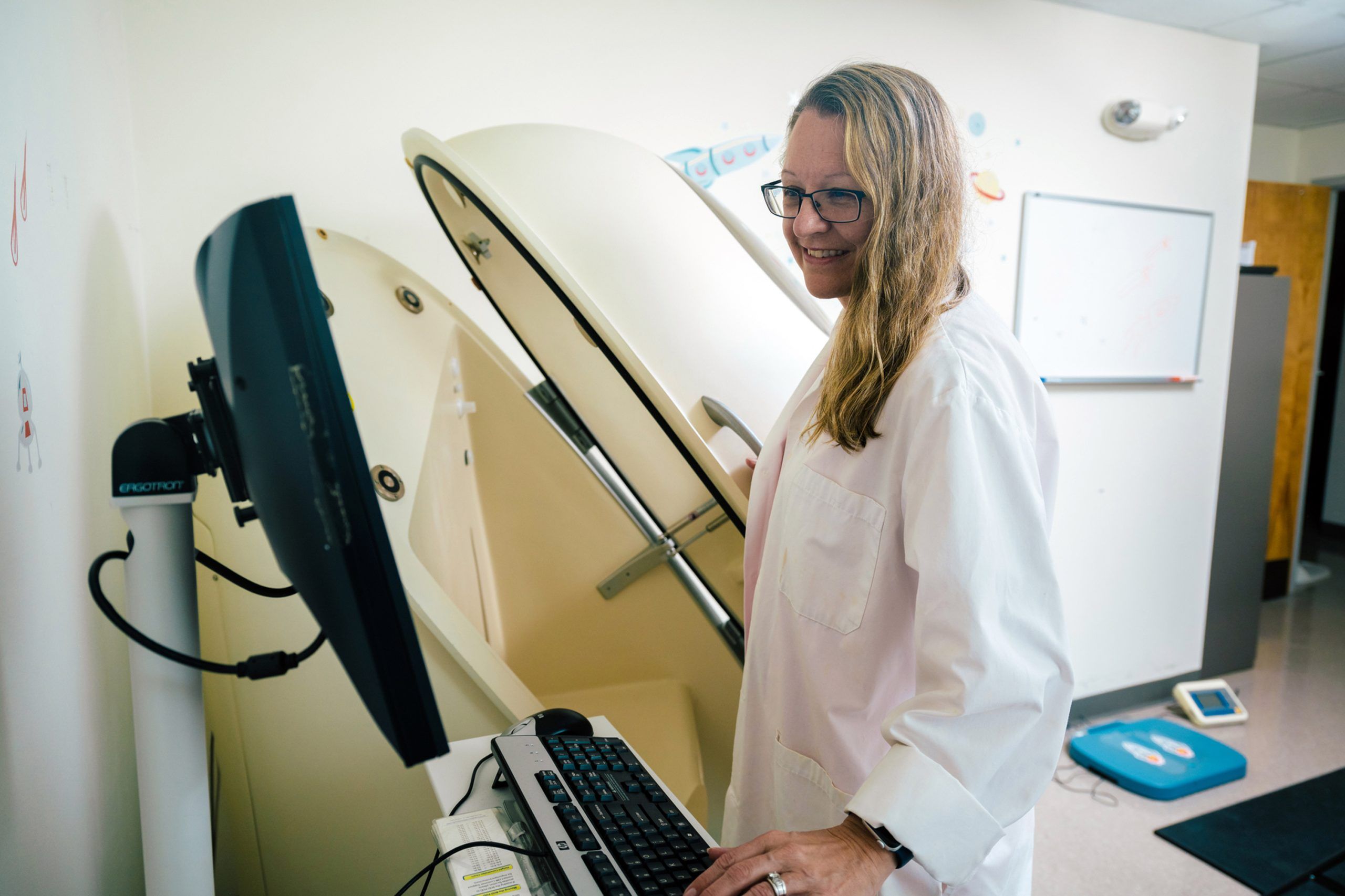

The Jefferson-Pilot Excellence Professor in human development and family studies served as lead author on the paper. Coauthors included Dr. Cheryl Buehler and graduate student Yu Chen in the same department as well as Safrit-Ennis Distinguished Professor Laurie Wideman in kinesiology and Dr. Lenka Shriver in nutrition.

Infants who gain weight rapidly before the age of two are at a higher risk for childhood obesity.

Given that the childhood obesity epidemic has not yet abated – over 37 million children across the world are obese – scientists are parsing out which behaviors and practices are spurring infants’ rapid weight gain.

What’s for dinner, baby?

UNCG researchers bring evidence-based strategies to support parents and babies, both locally and globally.

This set of findings is the most recent publication from UNCG’s NIH-funded Infant Growth and Development, or iGrow, study – a $2.8 million longitudinal research program to better understand children’s obesity risk by tracking infants’ biological and social development from before birth until age two. The first aim of the iGrow study focused on determining the main predictors of infants’ rapid weight gain by studying infants from before birth to approximately 6-months of age.

Researchers recruited 299 pregnant women and measured their physical and psychological health, known as prenatal psychobiological risk. Strengths of their sample include the diverse backgrounds and socioeconomic statuses of participants: 29.4% identified as Black, 6.7% as multiracial, and 7.7% as Hispanic or Latino.

The researchers discovered obesogenic feeding practices strongly and significantly correlated with infant rapid weight gain, and that mothers’ prenatal psychological risk increased the likelihood they would engage in obesogenic feeding.

But, to their surprise, they found infants’ psychobiological risk was not significantly associated with rapid weight gain when considered within a broader model with feeding practices.

“Usually in research, we are most interested in what associations are statistically significant,” Leerkes says. “In this case, the ones that were not were also of interest.”

While the findings highlight the importance of parents reducing obesogenic practices, Leerkes says it is important to understand barriers families may face with infant feeding.

“Parenting a baby is so challenging. Parents are frequently exhausted and overtaxed between family and work commitments and ongoing stressors, and they are presented with lots of information which can be hard to weed through.”

Although breastfeeding is recommended to decrease obesity risk, some parents may not have this option due to time constraints, physical limitations, or other systemic level barriers.

“A variety of factors, including cultural and socio-environmental, can make it difficult for some women to breastfeed their babies,” says Shriver.

“Our findings show that new parents can still prevent excessive weight gain in the first few months of their child’s life even if breastfeeding is not a realistic option for them.”

They recommend parents who are bottle feeding stay attuned to their baby, including watching for signs their baby could be full, observing suckling rate, and turning off the television. They also advise parents to avoid adding cereal, juice, or baby food to a bottle and to try not to use a bottle to soothe a baby that is not hungry.

The new publication represents the first set of findings testing one of iGrow’s primary aims, and the researchers look forward to many more to come.

With an additional $3 million in NIH funding, the iGrow study recently expanded to include iGrowUP. Now, UNCG researchers can follow the participants all the way to the age of five, giving them a unique, longitudinal vantage point into obesity risk throughout infancy and early childhood.