“People don’t always intend to be organizers. You see something, it hurts you, it touches your heart, and you move.”

“People don’t always intend to be organizers,” says Joyce Johnson. “You see something, it hurts you, it touches your heart, and you move.”

Partnerships. With the 30-year-old Beloved Community Center, in support of economic, social, gender, and racial justice. With Neighborhood Markets and the Guilford Urban Farming Initiative, to combat food insecurity. With the Greensboro History Museum and the Greensboro Library, to elevate civic conversations and make more learning more accessible.

That’s what lies at the heart of the National Communication Association’s Center for Communication, Community Collaboration, and Change – or NCA-CCCC, which launched at UNC Greensboro in 2019.

Why is NCA-CCCC here? That’s thanks to Greensboro’s long, proud history of community action and UNCG’s reputation for impactful collaborations.

When the NCA announced its largest grant ever – funding communication research involving partnerships between an academic institution and its local community – department head Dr. Roy Schwartzman, Dr. Spoma Jovanovic, and other faculty members in communication studies knew that UNCG was the perfect fit.

“Our university is known for its emphasis on community-engaged research, commitment to service learning, and history of partnerships with local nonprofits,” says Schwartzman.

The NCA agreed.

With the grant and matching University funding, the team established the NCA-CCCC to build on existing partnerships – and create new ones. The center’s theme: to cultivate resilient communities.

They chose that focus, says Jovanovic, “because we’re seeing a lot of social crises that seemed to be chronic, that are really threatening the ability of various populations to thrive.”

Large income disparities, food hardship, aggressive voter suppression laws, racial violence, and incidents of insufficiently redressed police violence – all erode confidence in social institutions and threaten the resilience of communities.

These problems cannot be solved from the outside in or the top down.

“We have to build upon the strengths of our community – through people and grassroots organizers,” says Jovanovic. “The people are the spark, the ones who have the direct experience, who can say that things need to be different. Tapping into that is how we find the greatest opportunity for progress.”

As the NCA-CCCC scholars and their partners began work, the COVID-19 pandemic hit, adding to and amplifying the inequities they hoped to dismantle.

The center theme of resilience seemed almost prescient. “We all had to expand our capacity to address adversity,” says Jovanovic.

Fortunately, these are not people who back down from a challenge.

Everybody Eats

Neighborhood Markets in Greensboro

Every Saturday at 7:30 a.m. in a church parking lot in Sunset Hills, next to UNCG’s campus, farmers unpack their produce, alongside bakers, relish makers, and meat vendors. A similar group sets up on the other side of campus, in the Glenwood neighborhood, on Thursday evenings.

The two locations joined efforts four years ago to form the nonprofit Neighborhood Markets and launch the Green for Greens program, which allows Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program – or SNAP – beneficiaries to shop at farmers markets by doubling their funds for fresh food.

The program not only expands who can shop at farmers markets and have access to fresh food, but also boosts the local economy by putting money into the hands of small farmers and entrepreneurs.

In Glenwood, market manager Liz Seymour (third photo above) runs the cards and hands out the wooden tokens as co-manager Shante Woody leads the set-up. In Sunset Hills, the work falls to co-managers Kathy Newsom and Stephen Johnson, with assistance from UNCG’s Dr. Marianne LeGreco.

For more than a decade, LeGreco has been one of the driving forces behind local food security initiatives, including urban garden projects, fresh food mobile markets, entrepreneurship programs, and culinary workshops.

In 2015, the Greensboro and High Point area was identified as the most food insecure area in the nation. As Green for Greens and similar initiatives were put into place, the area’s food insecurity ranking fell by eight percent.

“It’s hard to look at some of these things in isolation,” LeGreco says. Her 2021 book “Everybody Eats,” co-authored with Dr. Niesha Douglas, uses case studies in Greensboro to analyze the infrastructure of food justice. “When we’re thinking about food insecurity, it’s about building a stronger system. All of the pieces work together.”

Food insecurity has climbed again during the pandemic. The Neighborhood Markets responded by ensuring they were categorized as “essential businesses” that could remain open. UNCG students facilitated listening sessions with vendors and shoppers to identify changing needs, resulting in new options such as online ordering and drive-by pickups.

The scholars also gathered data, finding that the markets boosted financial security and provided community connections – during the pandemic and also during racial and political tensions brought up by instances of police brutality.

“It was a way that people could still gather, decompress, and talk about what was going on,” says Newsom. “In some ways it was a payoff for a vision, to be there at a time when the community needed that kind of connection.”

Tools of Democracy

Through 2020 and 2021, the Greensboro History Museum, with Dr. Jenni Simon, Dr. Christopher Poulos, Dr. Jovanovic, and their students, hosted nine city-wide public conversations on three topics: voting and democratic participation; police, community, and justice; and housing and equity.

They weren’t your typical conversations. “The guidelines for Democracy Tables are based on what’s called intensive dialogue,” explains Poulos, whose research focuses on connections between dialogue, openness, and trust. “Rather than engaging in argument, we speak from our own point of view and listen deeply to others.”

They use a three-round structure that begins with conversation about where participants are from and their knowledge base, followed by a deeper dive into the topic, and then a wrap-up and formulation of questions.

“It’s storytelling, a personal experience,” explains museum curator Glenn Perkins (third photo, center), who received his graduate degree from UNCG. “So, if the topic is voting, we’re asking people to talk about the first time they voted, and why voting is important to them. What are some challenges that they’ve run into in registering to vote or making sure their vote counts?”

Follow up events with subject experts addressed questions raised by table participants.

The project aims to engage community members, especially those from underrepresented backgrounds, and to strengthen community leadership – giving citizens tools to influence city policies and governing processes.

Responses from the Democracy Tables and surveys fed into infographics to be shared with decision-makers in Greensboro – and a museum display is under development by a UNCG museum studies graduate student. The researchers also presented their work at

a 2021 Smithsonian conference and are preparing a manual for other museums interested in pursuing similar experience-based dialogues.

Beloved Community

Joyce Johnson, Reverend Nelson Johnson, and Dr. Spoma Jovanovic at Beloved Community Center

The Beloved Community Center, which has served the region for over three decades, takes its name from the “Beloved Community” Martin Luther King Jr. spoke of achieving through nonviolent dialogue and universal cooperation.

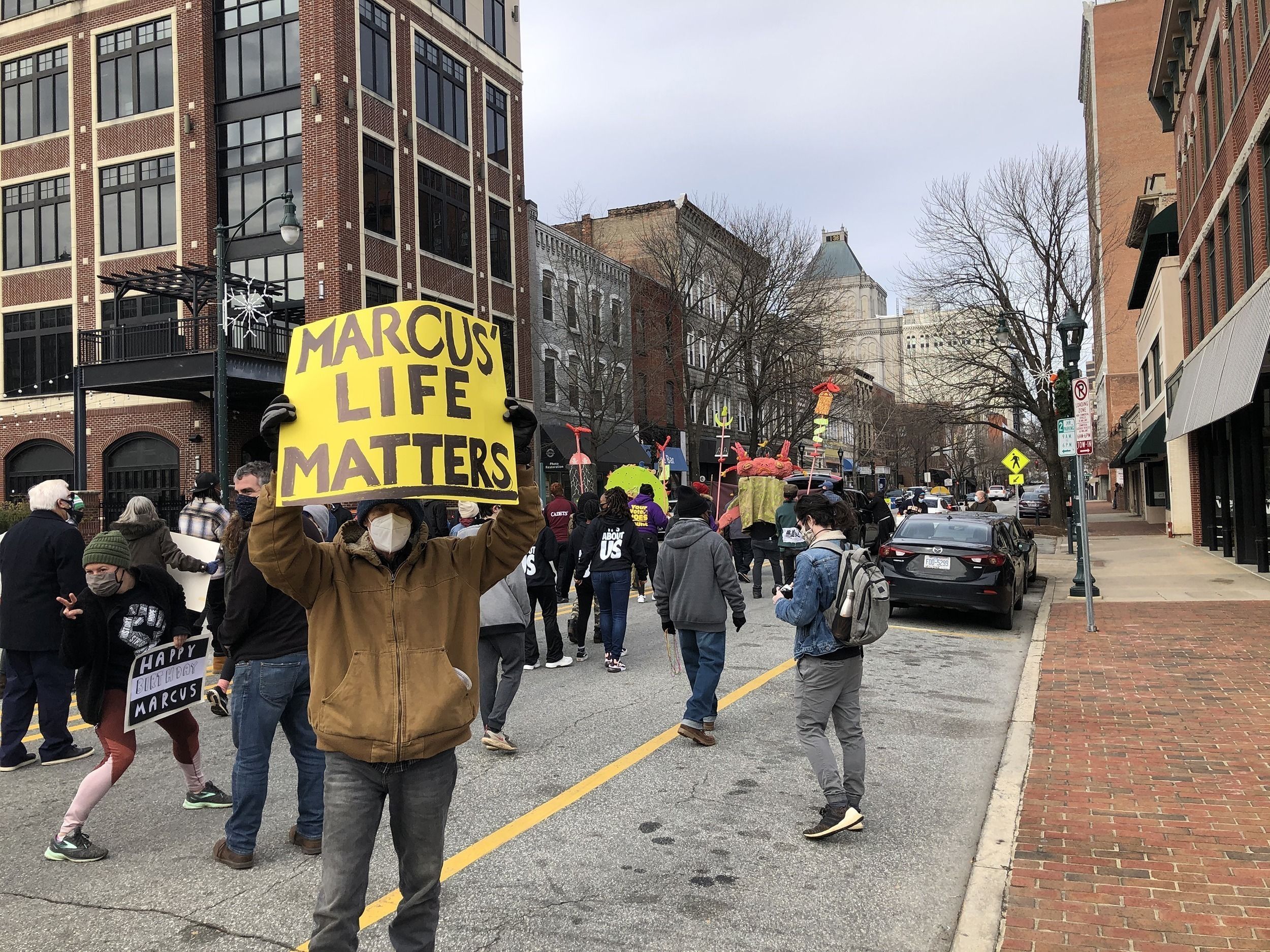

At noon-time Community Tables and evening events, community members – including local elected officials, business owners, students, and people who are homeless – talk candidly on matters of justice that require collective action. In recent years, discussions have revolved around policing, including what led to the homicides of George Floyd and, locally, Marcus Deon Smith.

“Beloved has a real open-door policy, which means we have to take on really challenging questions and things that divide us,” says Joyce Johnson, who is one of the leaders of the Beloved Community Center, or BCC.

“Despite divisions, we learn how to talk with each other, work with one another, hear each other, to figure out how we share this space on Mother Earth, so that I’m not diminished, and you’re not diminished. So that together we have something that we call the love of community.”

Jovanovic, along with her colleagues and students, has worked with the center and conducted research on its actions for over 15 years.

Johnson and her husband Reverend Nelson Johnson are survivors of the 1979 Greensboro Massacre, when five workers’ rights activists were killed. In 2004, the BCC helped establish the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission to seek justice for the event – it was the first commission of its kind in the nation and, in 2020, led to the Greensboro City Council releasing an apology.

Among the first scholarly products of Jovanovic’s relationship with BCC was her 2012 book “Democracy, Dialogue, and Community Action: Truth and Reconciliation in Greensboro.”

The BCC’s veteran organizers always welcome new voices, so they can share what they’ve learned over time and help facilitate action and understanding.

“A lot of the focus has been on democratizing systems and processes and preparing students to enter this world,” says Jovanovic, who recently edited the Rowman and Littlefield book “Expression in Contested Public Spaces: Free Speech and Civic Engagement.”

“What we’ve seen in the rise of Black Lives Matter illustrates how much people want to have a say in their society’s structure.”

UNCG faculty and students have helped develop and refine communication strategies and storytelling techniques for BCC.

Greensboro protest photo courtesy of Spoma Jovanovic

“Part of the gift of this relationship with UNCG’s communication studies department,” says Johnson, “is that so much of what we do requires communication, storytelling, really listening, hearing, understanding, and then being able to translate that into action.”

Johnson and Jovanovic say that what sets BCC apart is its ability to keep connecting people and to keep moving society in a more equitable direction, during times of widespread social unrest, through calm periods, and over decades.

“People don’t always intend to be organizers,” says Johnson. “You see something, it hurts you, it touches your heart, and you move. But then you might move on. What Beloved does is provide continuity.”

Democratization of Learning

Dr. Cristiane S. Damasceno first participated in the international Learning Circles project when it was piloted at the Chicago Public Library in 2015.

“They’re different from college classrooms, where experts are in charge of things,” she says. Instead, students direct learning together and “group interactions prompt them to cultivate the skills to learn independently.”

Now, Damasceno and her colleagues are working with Greensboro Public Library to host Learning Circles locally.

The project relies on materials and logistical support from Peer 2 Peer University, a global network that developed early Massive Open Online Courses and works with organizations worldwide to promote free access to information and self-guided learning. In the free study groups, a facilitator, who does not need to be a content expert, keeps conversations flowing.

“It’s that open-source model,” says the library’s specialist Beth Sheffield, who manages the program. “You take any kind of class and come together, access the material, and learn together. The library provides the framework. For us, it’s about how can we make material accessible to people and meet them where they are.”

In the last two years, learning circle topics – chosen through community member surveys – included healthy cooking, American Sign Language, jobs skills, technical support, coding for kids, poetry, and “21 Days of Racial Equity and Social Justice,” which was offered three times because of its popularity.

Circles have been mostly online during the pandemic, but some were offered in person at a Greensboro Urban Ministry-managed apartment building for those who have recently experienced homelessness.

The research team has produced reports on the work with recommendations and a training guide, available on the Peer 2 Peer website. “Initiatives like these,” says Damasceno, “are transforming the ways people learn together and redefining the educational landscape for the 21st century.”

Shared Ground

St. Philip Garden of Peace

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day in 2021, volunteers broke ground for a neighborhood agriculture project in Southeast Greensboro, with the Guilford Urban Farming Initiative. The land is part of St. Phillip AME Zion Church, a main partner on the project to establish “St. Phillip Garden of Peace.”

“We wanted it to be not only a garden of sustenance, but a place of peace,” explains Pastor Lisa Caldwell, who facilitated the use of the land and involvement of congregant volunteers, many of whom grew up in the neighborhood.

Dr. Etsuko Kinefuchi (second photo) and her UNCG students are volunteering in the garden and conducting surveys with St. Phillip neighbors, to gauge their level of interest in the garden and in farming, and their attitudes about protecting the Earth.

Kinefuchi studies ecological approaches to culture, identity, and communication.

“An eco-justice lens is tied to social justice,” she says. “So, the garden is a good way to look at that – food access as a social justice matter, but also ecojustice, cultivating the land sustainably.”

ADA-accessible raised beds stand alongside open in-ground vegetable plots. There’s a greenhouse, and garden designer Brandon King has included areas for a children’s garden, flowers, pollinators, and fruit. Seeds, plants, and supplies come from the agricultural extension office, the Guilford County Prison Farm, and Truist Bank, with the NCA-CCCC filling in some funding gaps.

On workdays, acting farm manager Nathan Lewis (second photo) and project director Paula Sieber share their knowledge with volunteers about basic gardening and sustainable practices. One goal is to help more people achieve what is known as “food sovereignty” or being able to control their own nutritious, culturally appropriate food supply.

“Most of us aren’t anywhere near food sovereign,” says Lewis, who joined the Guilford Urban Farming Initiative with more than seven years of farming experience. “It starts with saving seeds and using them to grow your own food. It’s not a very common skill anymore, but there are sustainable cycles you can maintain.”

They use organic permaculture methods for pest control and fertilizing, and guild – or companion – planting to support the crops. Composting helps with soil nutrient cycling. “Responsible farming can regenerate the landscape,” says Lewis. “We’re capturing more carbon with the garden.”

Along with volunteer days, the garden hosts tasting events for the neighborhood, to show what can come out of the garden.

“To see people getting healthier, eating better, to see people provide for themselves, has been the journey,” says Caldwell.

Below: UNCG Center for Communication, Community, Collaboration & Change leaders (left to right) Dr. Marianne LeGreco, Dr. Cristiane Damasceno, Dr. Christopher N. Poulos, Dr. Spoma Jovanovic, Dr. Jenni Simon, Etsuko Kinefuchi, and Dr. Roy Schwartzman