Dr. Jennifer Etnier recently gave her 79-year-old mother a smartphone. Her mother’s memory is almost impeccable, and Etnier knew she would quickly adapt to the technology. Her father, on the other hand, is in the early stages of late-onset dementia.

One difference between the two? Exercise. Throughout her life, Etnier’s mom has maintained high levels of physical activity. By contrast, her dad was active as a younger man, but let his exercise decline in his later years.

“I started wondering if their differing exercise patterns contributed to this phenomenon,” says Etnier, now the Julia Taylor Morton Distinguished Professor in the Department of Kinesiology at UNC Greensboro.

It’s that curiosity that has guided Etnier’s research since she arrived on campus in 2004, put her ahead of the curve in her field, and led to her latest $3.4 million National Institutes of Health study.

The funding will support Etnier and her fellow researchers as they work to determine what effect exercise might have on middle-aged and older adults with a genetic risk of Alzheimer’s disease – a leading cause of death in the U.S. They hypothesize that those with a family history of dementia or Alzheimer’s disease can cognitively benefit from exercise.

“Dementia is a term used to describe cognitive declines serious enough to interfere with daily living,” says Etnier, who is a fellow of the National Academy of Kinesiology and the American College of Sports Medicine.

“Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia and is characterized by the death of neurons in the brain.”

It’s a fear woven deep in the fabric of humanity, and especially prevalent as we age: the fear of suddenly losing your ability to think and process – to remember. And the fear is valid, as the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease – a specific form of dementia – is on the rise, with no known cure or pharmacological interventions to prevent the disease.

Etnier gets that, and her work is proving that we can do something about it. She’s already discovered that long-term physical activity is beneficial for older adults with a family history of Alzheimer’s, regardless of their genetic risk for the disease.

In 2013, Etnier and team conducted their first Physical Activity and Alzheimer’s Disease research study, or PAAD, with $394,625 from the NIH.

In the original PAAD study, Etnier and her fellow researchers observed that exercise correlated with improvements in memory, with effect sizes ranging from small to large.

“If you think of a test where the average grade is 70 and the standard deviation is a 10, essentially we found that exercise increases your performance on that test by between 2.7 and 10.5 points,” Etnier said. “If it increased it by the largest amount, that would be like increasing your ‘grade’ by a full letter grade.”

The initial study was small – with 54 subjects – and lacked a control group for comparison, thus limiting the researchers’ ability to definitively say that changes in memory were in response to the exercise.

This time around, in PAAD2, Etnier is including a control group and also wants to find out whether or not there are genetic variables that identify people who might benefit more from exercise than others. She is looking at the apolipoprotein E, or APOE, genotype as a potential variable to determine how much one can benefit from exercise. The APOE genotype is a predictor of Alzheimer’s.

After the age of 30, cognitive decline begins even in healthy adults. But people with a genetic predisposition or family history of Alzheimer’s may be experiencing these declines at a faster rate.

“We know the brain is malleable across the lifespan. Although the brain is more plastic – able to change in response to experiences – at young ages, it is still plastic even in older adults,” Etnier says. “Physical activity is important at all ages – but the benefits may be even more critical as you get older.”

Improved cognitive performance in 8 months. Etnier’s team has found that participating in a regular exercise program for as few as eight months is associated with improved memory performance in older adults.

Among those at genetic risk for Alzheimer’s, the researchers also observed alterations in brain function.

Participating YMCAs provide exercise instruction and help collect participant data, such as heart rate and ratings of perceived exertions. UNCG Associate Professor and exercise physiologist William Karper provides regular oversight at the YMCA locations to ensure uniformity across the programs. Above, PAAD2 participants work out at the Kathleen Price Bryan Family YMCA, with guidance from graduate student Delaney Thibodeau. See more photos on UNCG Research Flickr.

ON THE MOVE

Etnier and her team are now working to recruit 240 people from Guilford and surrounding counties over the next three years. Unlike other studies looking at physical activity for prevention of Alzheimer’s disease, PAAD2 focuses on a younger age group – 40- to 65-year-olds – and will utilize group exercise instead of solo exercise. These factors help distinguish the study from any other in the country.

“If an individual is cognitively normal when they are 60-80 and have both a family history of Alzheimer’s and a genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease, then they may have some other genes in their make-up that are giving them protection against Alzheimer’s,” Etnier says. “By targeting a younger cognitively normal group, we hope to bypass that issue.” The researchers also hope using a group exercise program will offer participants social support.

Participants undergo testing at the beginning, middle, and end of a year-long period, to measure thinking abilities, brain structure and function, and biomarkers related to Alzheimer’s disease.

Half of study participants commit to an hour-long exercise program of walking and training with resistance bands three times a week for a full year, while the other half continue living their normal lives without regular exercise. Importantly, at the end of the study year, participants in the control group receive a short-term YMCA membership to encourage them to get active as well.

Executive Director David Heggie of Greensboro’s Bryan Family YMCA helped Etnier secure partnerships with YMCAs in Alamance, Davidson, Forsyth, Guilford, Randolph, and Rockingham counties for the project’s exercise programs.

The benefits of a single workout. Etnier’s team has found that a single 20-minute session of moderate-intensity exercise produced significant benefits for both short-term and long-term memory.

ALL IN THE BRAIN

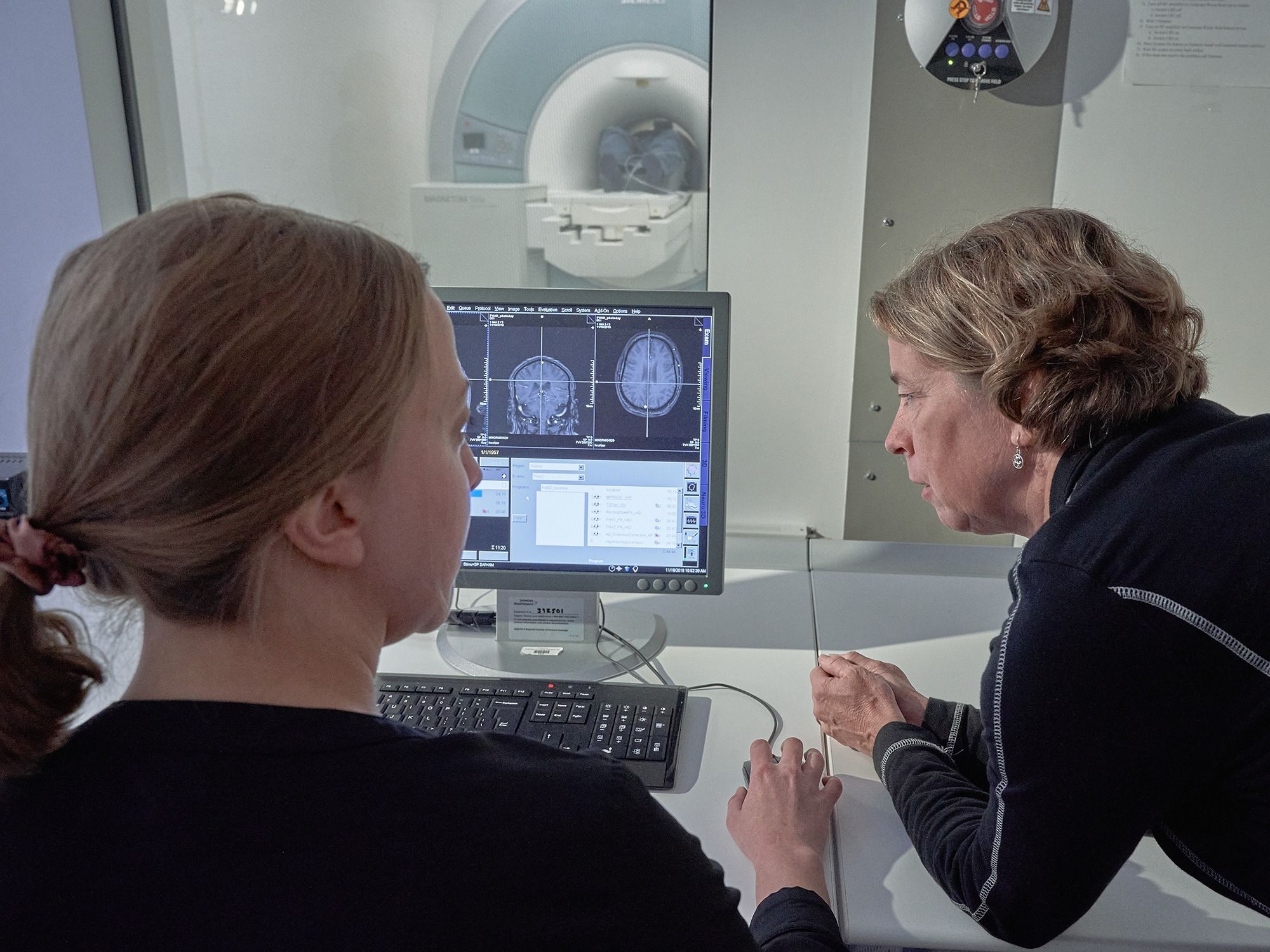

In her undergraduate and graduate studies in clinical exercise physiology, Dr. Alexis Ganesh (first photo, right) developed a passion for understanding the aging brain. She chose UNCG for her doctoral studies specifically to work with Etnier (second photo, left).

“From the first day of my doctoral program, I was excited to use the MRI scanner,” says Ganesh. She was soon designing studies around the technology and learning to analyze brain images. Now, as a postdoctoral fellow, she’s responsible for neuroimaging on the PAAD2 project.

She values the opportunities and training she has received here, she says – not just on the MRI but also on effectively communicating her results to scientific peers and the community.

BENEATH THE SURFACE

“What’s intriguing about the measures we’re taking is that the behavioral measures are not likely to be the most sensitive ones we have,” says Etnier. “The ability to perform a task may or may not change over the course of a year, but brain structure and blood biomarkers are very sensitive.”

Etnier works with Dr. Laurie Wideman, Safrit-Ennis Distinguished Professor in Kinesiology, to take blood samples at pre- and post-test appointments. They are looking at blood-based biological markers relevant to Alzheimer’s and exercise.

Etnier is also using the University’s Gateway MRI Center to assess brain structure and function.

“When you compare yourself to someone else, there are a lot of factors – like lifestyle, environment, and genetics – that might affect your brain structure and how it functions,” says Dr. Alexis Ganesh, the postdoctoral researcher responsible for the project’s neuroimaging. “We suggest that physical activity can provide benefits, but the degree of benefit may depend on where you’re starting.”

High-resolution MRIs of participants’ brains show structural volume of brain regions, while functional imaging allows the team to see neural activation during tasks and investigate how functionally connected the brain is.

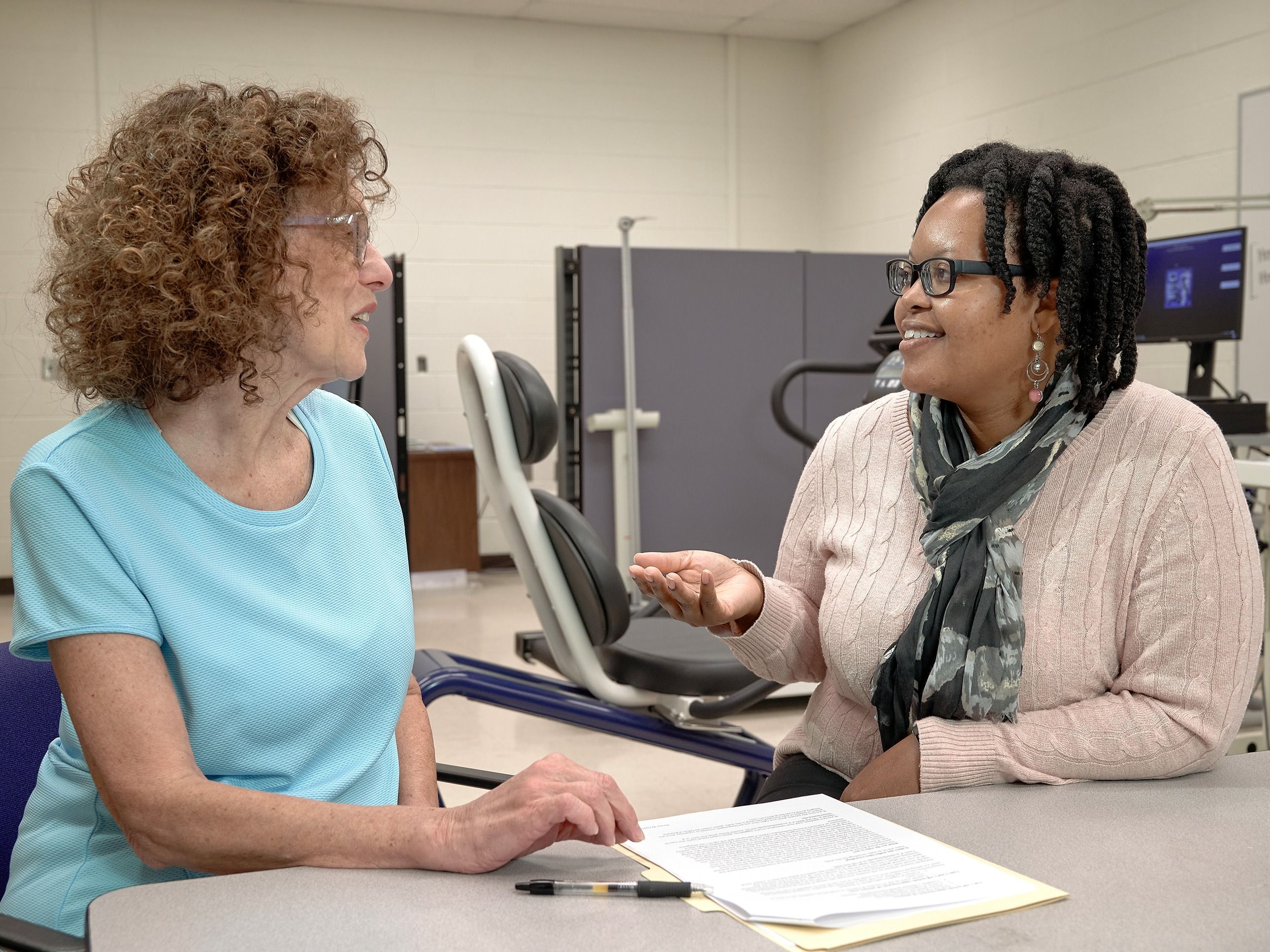

Shonda Mobley (first photo above, right), who received her master’s in public health education at UNCG, serves as the PAAD2 project coordinator. Her responsibilities include screening and scheduling participants. Postdoctoral students and graduate students takes blood samples and run participants through cognitive and fitness tests at the beginning, middle, and end of the year-long study. See more photos on UNCG Research Flickr.

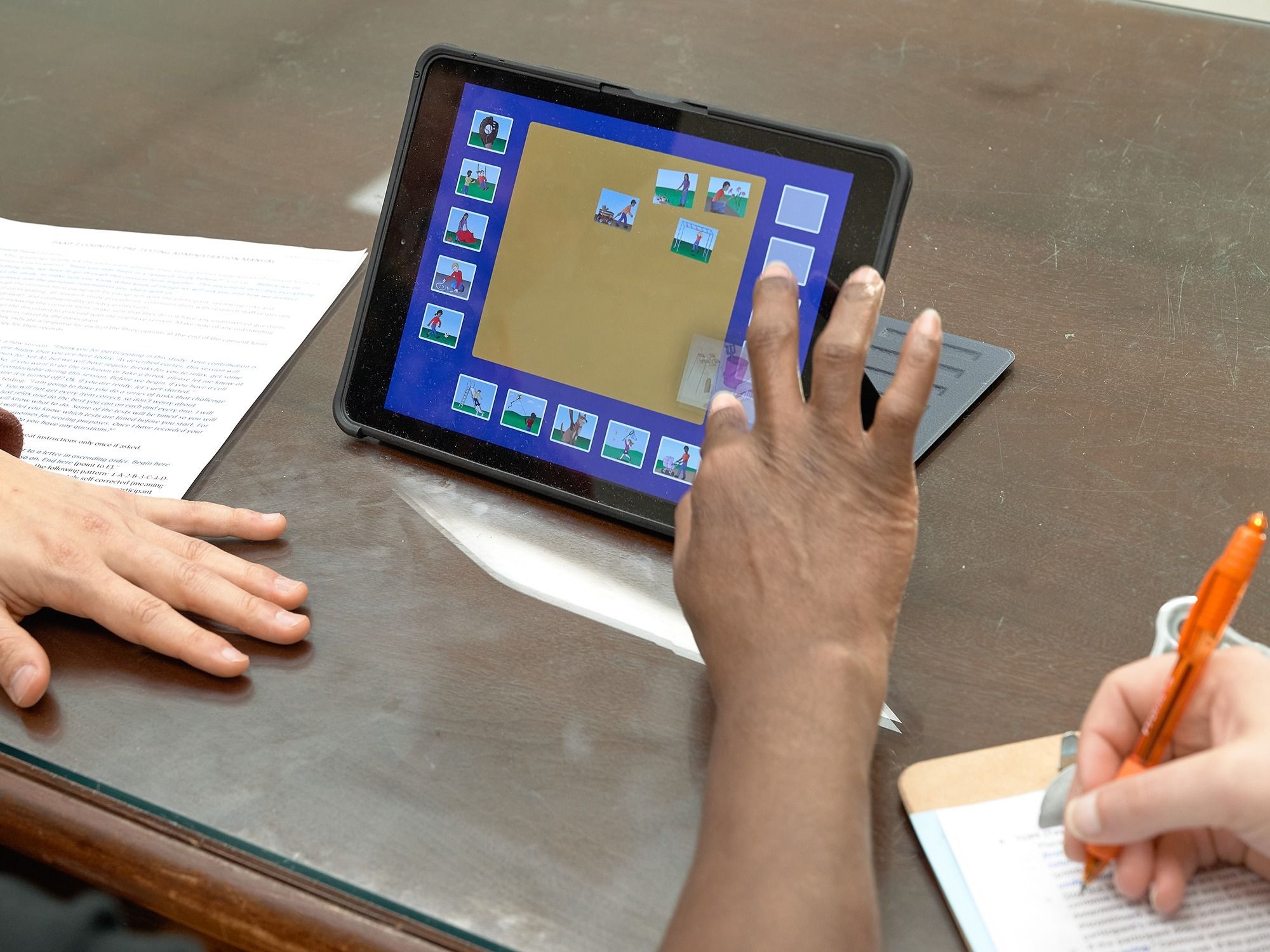

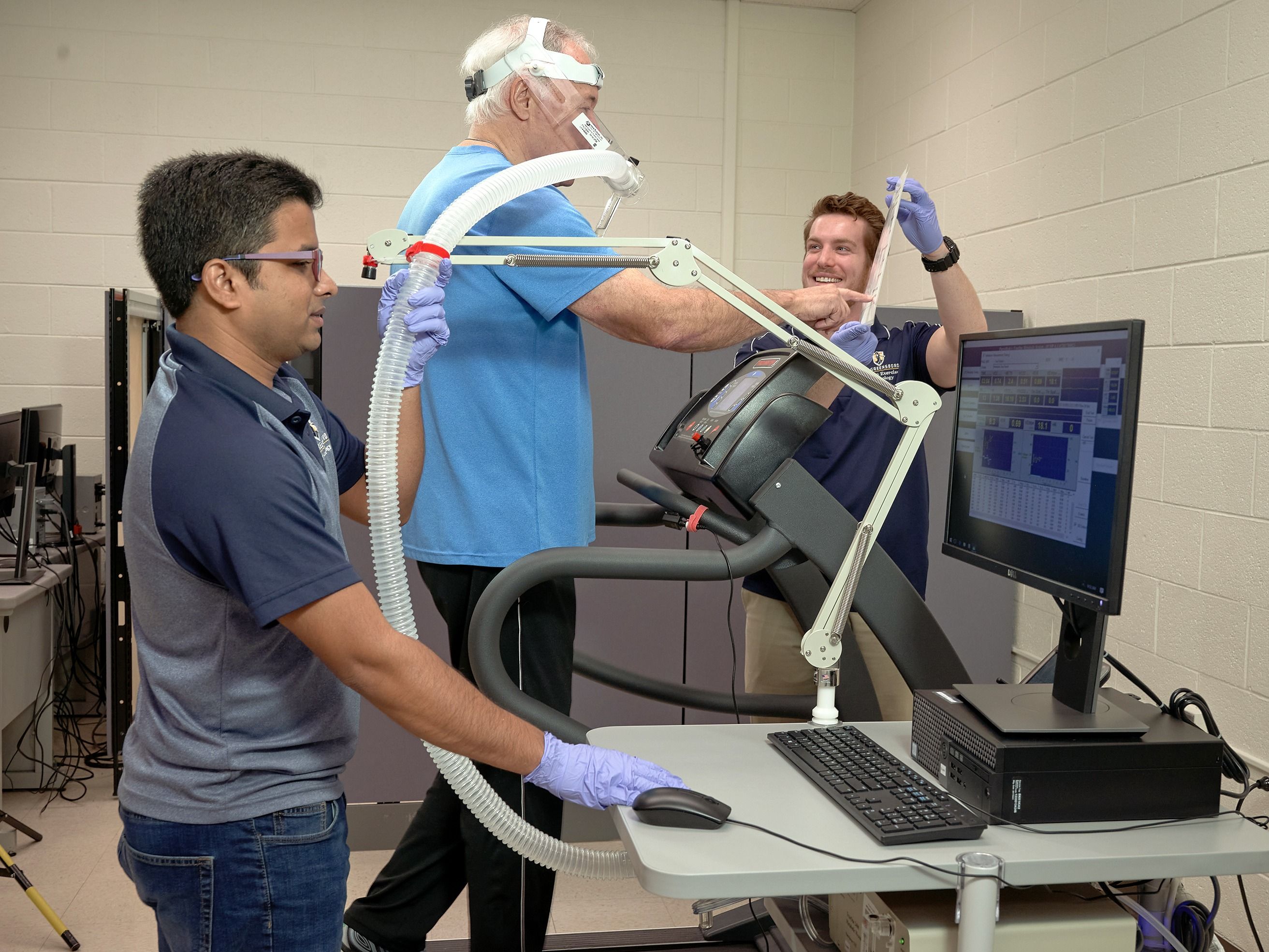

Above, postdoctoral fellow Kyoungshin Parks (right), runs a staff member through one of the study’s cognitive tests. Below, graduate students Towfiqul Alam (far left) and Sam Kibildis (far right) evaluate a participant’s fitness by measuring respiration and perceived exertion during exercise. See more photos on UNCG Research Flickr.

Changing Lives

“Physical activity may give you the protection you need to stall the onset of clinical impairment or to prevent it altogether,” Etnier says. “If we can delay the onset of Alzheimer’s by five years, that’s five more years with better quality of life – that’s five more years with your children and grandchildren.”

It was a radio ad asking for PAAD2 study participants that got Ginny Ebert’s attention.

“I was excited right away,” she says. “It touched home.”

Ebert’s grandmother and father have Alzheimer’s, and at 50, she’s pretty sure she’s on the way. Her mind feels like a pinball machine, she says. Things that once came easily are now more difficult, and she has trouble processing and making connections. Then she forgets what she’s trying to figure out in the first place.

Ebert graduated from UNCG in 1990 with a degree in nutrition, and throughout most of her life she was very active – swimming, running, and weightlifting. But then she took a long hiatus.

She began the PAAD2 exercise program in August, and so far, she has felt a lot better, both mentally and physically. But the thing she values most is the community she has built with the other participants.

“Getting to meet other people in a similar situation has created a supportive and positive environment,” Ebert says.

Community is just a small piece of the enormous impact Etnier’s work could have on both individuals and the future of Alzheimer’s research.

“I hope that once we finish the PAAD2 study, we can give people at risk the tools they need to potentially delay or even prevent the onset of this disease,” Etnier says. “If our expectations are realized, this could give hope to the millions of individuals who have seen a family member suffer the heart-wrenching effects of Alzheimer’s disease and who may fear the same fate because of their family history.”

To find out how you and your loved ones can participate in PAAD2, visit go.uncg.edu/PAAD2.