Dr. Claudia Cabello Hutt often compares her current research project to a Netflix series.

It’s full of drama, romance, and world travel. Eight countries, three languages, and six main characters.

The associate professor of Spanish is tracing transnational relationships among female artists, writers, and patrons of the arts who lived between the 1920s and late 1940s. She’s focused on queer women — those who rebelled against norms of sexuality, reproduction, and economic dependence — from Latin America, Spain, and the United States, and the networks they built.

Many of these women were expelled from their families or social groups because of their choices. As a result, they built “queer networks of exchange” — groups that, until now, have never been studied. “These anti-institutional spaces have emotional, intellectual, sexual, and economic functions,” Cabello Hutt says. “My goal is to theorize how these queer networks function and how they impact the cultural field.”

In doing so, she’s bringing to light the works and lives of women who have helped shape cultural history — putting them on the map figuratively and literally. Her work will ultimately culminate in a book, but she’s also creating a public, digital map tracing people, places, and connections.

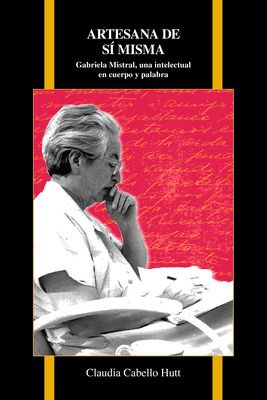

Cabello Hutt first discovered these queer networks while working on her book “Artesana de sí misma: Gabriela Mistral, una intelectual en cuerpo y palabra,” or “Artisan of Herself: Gabriela Mistral, an Intellectual in Body and Word.” The novel take on the Nobel laureate, published in March by Purdue University Press, has been highly anticipated in the subject’s home country of Chile.

“After Mistral died, the public intellectual side of her was buried and forgotten, and she became heavily idealized — portrayed as perfect, devoted, humble,” Cabello Hutt explains. “I try to unpack the myths and misinterpretations. She was very ambitious. She didn’t want to dress like most women. She was queer. Her complexity is key to understanding how difficult it is to be a woman in a public space of power.”

As part of her research, Cabello Hutt read countless letters between Mistral and other women. She saw the ways in which Mistral was supported by her peers, and how Mistral supported others — from sending money to helping women find jobs and lodging. “I realized the power of networks in the equation of ‘making it,’” she says. “You need to have allies around, especially if you’re doing things differently.”

So, two years ago, as she finished her book on Mistral, she revisited the letters she had flagged and began a transdisciplinary, travel-heavy, logistically complicated project involving hundreds of unpublished letters, press clippings, photos, ship records, and interviews with descendants.

The research will serve as a resource for scholars in the fields of cultural sociology, art history, literature, and gender studies. It will advance the study of networks, and it will unearth stories of women who shaped literature and art — especially those who worked “behind the scenes.”

“Whenever we achieve something of importance, we never achieve it alone. We’re always working with others,” she says. “Often, the people who are not named are women and minorities. I’m especially interested in these individuals — those who enable the work. We need to talk more about them.”