Fall 2021 | Feature

STEPS TO SUCCESS

For students with ADHD, college can be an uphill battle.

The college years are when many of us take our first steps into adulthood.

“During this period, we learn behaviors that can put us on a trajectory for success – or failures – as adults,” says UNCG psychologist Dr. Arthur D. Anastopoulos.

“Demands for self-regulation really increase. You’ve got to manage your own academics, your finances, your meals, your health, your social life, your car – you name it.”

It’s a big developmental adjustment for all students, but for students with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, he says, “There’s an enormously larger gap.”

The convergence of increased demands for self-regulation, coupled with withdrawal or reduction of support services for ADHD, is a recipe for disaster.

Anastopoulos, who is one of the country’s leading authorities on ADHD in children, adolescents, and young adults, says that for the roughly 5% of college students with ADHD, college can be a kind of “perfect storm.”

In college, students with ADHD frequently stop taking – or lose access to – medication, as well as other help such as counseling.

Anastopoulos observed this firsthand at his ADHD clinic at UNCG. Launched to serve children in the community while offering opportunities for graduate student training and research, the UNCG ADHD Clinic began to receive a growing number of referrals for potential diagnoses among UNCG students in the early 2000s.

Some individuals with ADHD did well enough in high school to get into college, Anastopoulos realized, but then struggled.

“They were just hitting a brick wall,” he says. “I was really curious why these students were having such a hard time.”

In subsequent research, he found that college students with ADHD, on average, get lower grades, are less likely to stay in school for eight consecutive semesters, and have a lower quality of life compared to their peers without ADHD.

It’s a significant problem. At UNCG, 5% of the student population represents around 1,000 students – including 800 undergraduates. Across the UNC System, which has nearly a quarter of a million students, thousands of young people are affected.

In early 2011, Anastopoulos read a newspaper article that quoted then-UNCG Chancellor Linda Brady about student retention and graduation rate challenges. He realized he had part of the answer and reached out.

“I said, although I know it’s not the whole problem, I can guarantee you the students we see in our clinic are contributing to the retention and graduation concerns.”

That email led to the largest, longest, and most rigorous treatment studies of ADHD in college students ever done – and the creation of a proven intervention to improve their outcomes.

A community endeavor

Brady introduced Anastopoulos to a nascent UNC System research effort – involving East Carolina University and, later, Appalachian State University – to find ways to help students struggling academically.

That effort soon turned into the College STAR – supporting transition, access, and retention – initiative, with $891,000 in funding going to UNCG’s portion of the project. Support for the project came from the Oak Foundation and GlaxoSmithKline – and, in Greensboro, from the Bryan, Weaver, Cemala, Tannenbaum-Sternberger, and Michel Family foundations.

“It was a community investment,” says Anastopoulos.

UNCG’s part of the project focused on college students with ADHD, the group Anastopoulos spotlighted for the chancellor. That program was called ACCESS, or Accessing Campus Connections & Empowering Student Success, and began with 88 students.

A community endeavor

Brady introduced Anastopoulos to a nascent UNC System research effort – involving East Carolina University and, later, Appalachian State University – to find ways to help students struggling academically.

That effort soon turned into the College STAR – supporting transition, access, and retention – initiative, with $891,000 in funding going to UNCG’s portion of the project. Support for the project came from the Oak Foundation and GlaxoSmithKline – and, in Greensboro, from the Bryan, Weaver, Cemala, Tannenbaum-Sternberger, and Michel Family foundations.

“It was a community investment,” says Anastopoulos.

UNCG’s part of the project focused on college students with ADHD, the group Anastopoulos spotlighted for the chancellor. That program was called ACCESS, or Accessing Campus Connections & Empowering Student Success, and began with 88 students.

Therapy techniques

Because very little research on treatment for college students with ADHD existed in 2010, Anastopoulos based the new ACCESS program on two successful studies that employed cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT, to treat adults with ADHD.

“We extracted the main elements of those two adult programs and packaged them in a way that was developmentally appropriate for college students,” Anastopoulos says.

For college students, that included a strong dose of educating. Many of the students understood their ADHD the way it had been explained to them when they were much younger. Helping them understand the condition in an accurate, age-appropriate way was the start of helping them take control of it.

At the same time, behavioral therapies helped students adopt new habits to be more successful. These included things like using a planner to keep track of assignments or agreeing to meet with a friend in the library for regular study sessions.

Finally, cognitive therapy helped students think more accurately about difficulties, so they could avoid negative emotional states – staying away from what psychologists call “maladaptive thoughts.”

If a student does poorly on the first test of a semester, maladaptive thinking might spur them to think they’re not capable of succeeding in that class. The student might ruminate on that idea and sink into a depression, believing they’re destined to flunk out of college and fail at their goals.

Adaptive thinking, on the other hand, might help a student to realize it’s just one test in one class, and that doing poorly simply means that they should seek out extra help, perhaps by talking to the professor or using tutoring support available on campus.

ACCESS tools to improve outcomes

- knowledge

- behavioral strategies

- adaptive thinking

What does ADHD look like in college?

When you think of ADHD in students, you might be imagining children struggling to focus or acting impulsively. While these are traits you might see in college students, usually described as problems with “executive functioning,” Anastopoulos wanted a deeper understanding.

He secured a $3 million National Institutes for Health grant to examine outcomes among college students with ADHD, in collaboration with Dr. George J. DuPaul at Lehigh University and Dr. Lisa L. Weyandt at the University of Rhode Island.

Their project – the very first longitudinal study to focus on college students with ADHD – followed 456 first-year students, some with and some without ADHD, at multiple universities.

The study provided new insights not only into students’ academic struggles, but also social and personal challenges they face.

Among students with ADHD, a staggering 55% also had another diagnosis, usually a depressive disorder or anxiety. By comparison, 11% of students without ADHD had similar diagnoses.

“This emphasizes the importance of assessing for – and treating – more than ADHD,” Anastopoulos says.

Honing the intervention

As each semester passed, Anastopoulos and his colleagues fine-tuned their approach – changing how long the program ran and other variables.

“That was the beauty of the generous funding from the foundations,” he says. “It gave us three and a half years to create, test drive, and tweak.”

The program they settled on requires two consecutive semesters – longer than many other treatment programs – to address ADHD’s chronic nature.

During the first semester, participants meet weekly for 90-minute group therapy sessions. They also meet one-on-one with a mentor each week. Mentors reinforce what students learn in the group sessions and help connect the students with other resources on campus.

The second semester locks in the positive changes that students made during the first semester, with one group session and four to six mentoring sessions.

“We saw great results,” says Anastopoulos. “So it was time to take the intervention to the next step.”

In 2015, he partnered with Virginia Commonwealth University professor Joshua M. Langberg to evaluate ACCESS with multiple cohorts of students, across multiple campuses, over several years.

Their work was funded by a $3.18 million grant from the Institute of Education Sciences in the U.S. Department of Education, and they were among the 5% of awardees to receive funding on their first attempt.

It remains the largest randomized control trial of an ADHD intervention for college students – and the largest evaluation of a college psychosocial intervention – ever attempted.

Diagnosing ADHD

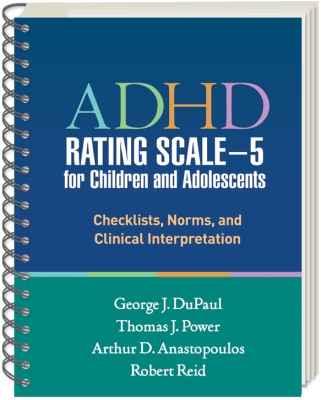

It was Anastopoulos, along with his colleagues Dr. George J. DuPaul, Dr. Thomas J. Power, and Dr. Robert Reid, who developed a standard ADHD diagnostic tool in 1998.

“There’s no simple or fast way to diagnose ADHD,” says Anastopoulos. “You have to gather data from multiple sources – and assess how well a person is functioning relative to their peers.” That complexity is why their tool, updated in 2016, includes questionnaires for teachers and parents, versions for children and adolescents, and separate profiles for boys and girls.

Their method, which has been translated into several languages, is widely used by clinicians, in schools, and in medical settings. It’s also used by many pharmaceutical companies seeking to measure the effect of their drugs on ADHD symptoms.

But Anastopoulos remains troubled by “the casual way some people still evaluate ADHD, especially frontline medical professionals who often rely on a single rating scale.”

He and his spouse Dr. Terri L. Shelton – UNCG Vice Chancellor for Research and Engagement and also a clinical psychologist – co-wrote the only book to-date that describes, step-by-step, how to rigorously diagnose and evaluate ADHD.

“Establishing a diagnosis is like putting a puzzle together,” he says. “If there are enough pieces, they will form a clear, unmistakable picture.”

Accessing success

The four-year study screened 361 students, enrolled some 250 students, and included a control group, where researchers compared students who got the intervention with those who received it on a delayed basis.

“We saw massive increases in their knowledge of ADHD, their use of behavioral strategies like time management, and also their adaptive thinking,” Anastopoulos says. As a result, ADHD symptoms went down, while executive functioning went up.

Students who received ACCESS services also reported feeling less stressed about managing their daily lives. While students in the control group reported an increase in anxiety and depression, students participating in ACCESS didn’t.

“Untreated ADHD is kind of like having a broken arm,” Anastopoulos says. “It’s not that you can’t be successful. It’s just that the broken arm is keeping you from being all you can be.”

The benefits endured, lasting at least six months after the program ended.

“Over the course of our treatment studies, we have already made a difference in the lives of hundreds of students,” says Anastopoulos.

Over the past year, Anastopoulos and his collaborators have created a treatment manual and series of training videos, to help other colleges and universities implement the program.

“We have had a lot of interest for us to provide training and bring ACCESS to other campuses,” Anastopoulos says. “We’ve also gotten calls from parents and students around the U.S.”

That means that work begun in Greensboro to help students with ADHD will be shared and potentially help thousands of college students across the country in the years to come.