Minutes into Billy Hawkains III’s film “By Fire,” and the pulsating rhythmic beat from the bongo and conga and the polyrhythmic sounds from the organ and high cymbals make you want to, well, dance. But then, that’s the point.

Hawkains, a dancer and choreographer, knows that the body wasn’t meant to be stagnant. “I see everything as dance – walking, swaying,” he says. He’s particularly fascinated by what he sees, and saw growing up, in the Black church.

“When I see people in church moving and shouting, my mind goes to dance,” he says. “’I do that in class,’ I say to myself.”

Those experiences inspired Hawkains’ MFA thesis project, the original choreo-graphed piece “By Fire.” What would have been an in-person dance production, required of all UNCG MFA candidates, moved to film due to the pandemic. But Hawkains didn’t see the shift to celluloid as settling.

“There are certain restrictions in a live performance that you can overcome with film,” he says. “The camera can take you closer in on the body as it moves. You can see the facial expressions, the hands. You can see all around the body.”

“By Fire” examines how the body can operate “as a vessel of transformation,” Hawkains says. He began the work by conducting historical research on the roots of physical movement as part of Black worship.

“I was highly focused on looking at Black bodies in the Southern Black church. Our bodies are a very important part of the service. The way that we sway and jump and clap and even sweat is important. Other churches aren’t like this – it’s tied to our history.”

In his studies, he found the ring shout, which was indigenous to much of Central and West Africa and practiced on plantations by slaves in the Southern United States and beyond. “They would form a circle, and, using their bodies as percussive instruments, they would bring their bodies to a moment of exhaustion. Through call and response, dancing, shaking, clapping, the body began to transform. It opened them up to something greater than themselves. It was something they could pour themselves into.”

It was also a way to remember home and deal with slavery’s brutality, Hawkains says. “They used their bodies as a form of resistance and perseverance. They are fighting for freedom. They leave with burdens lifted off their shoulders – because the Black body carries so much.”

But Hawkains wondered if the experience could be brought to people outside of the Black church. “There is a certain level of liberation and freedom that we all as human beings are reaching toward,” he says. “I wanted to know if this could be a universal experience.” To answer that question, he brought the ring shout into the dance studio, “working with Black bodies and non-Black bodies,” to conduct embodied research.

“The site for embodied research is the body itself,” he explains. “Dancers take elements, like from the ring shout, and instead of talking or writing about them, we embody them, we experience them.”

He worked with a team of dancers and percussionists, most students at UNCG. Each rehearsal would begin with elements from the ring shout, and the artists developed the movements from there.

The more they practiced and perfected the choreography, the more the dancers were changed. “What I saw, what we experienced was a freedom,” Hawkains says of his multi-gender and multi-racial troupe. For some it was a religious experience, for others a spiritual one. “It was the kind of freedom that comes from opening your body and mind and spirit.”

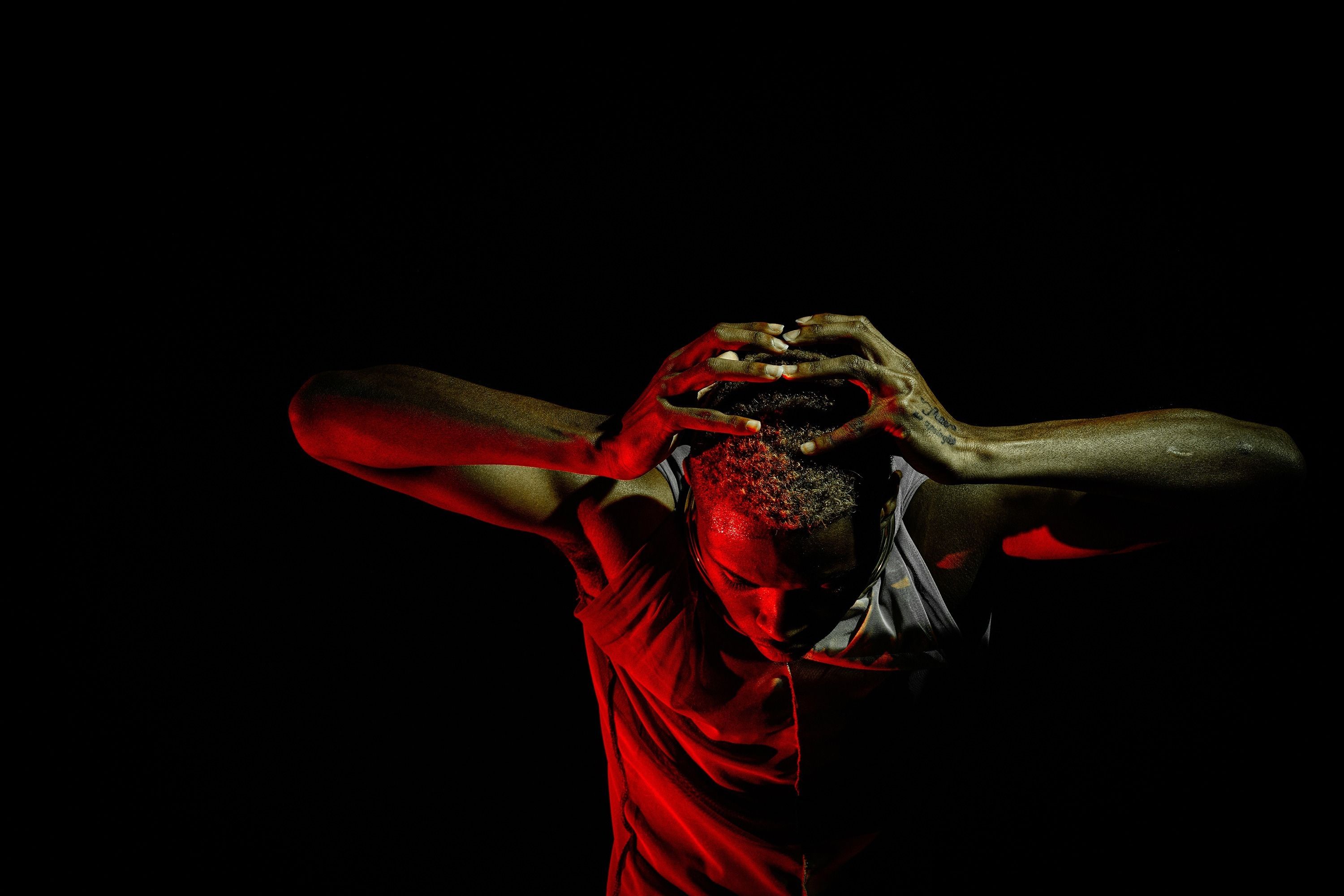

In seven months, the team of artists had created “By Fire.” The name is inspired by a biblical verse in Acts: “And divided tongues as of fire appeared to them and rested on each one of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit…” During the performance, Hawkains and his team dance through infusions of white and red smoke.

Hawkains’ work was supported by a competitive grant from UNCG’s Atlantic World Research Network and a scholarship from UNCG’s Kristina Larson Dance Fund.

His thesis chair was Professor Duane Cyrus. After graduating from the NC School of the Arts, Hawkains danced with Cyrus’ Theatre of Movement company, and it was Cyrus who suggested he apply to UNCG.

“When I think about this journey I’ve been on, I realize everything that happened was ordained,” Hawkains says. “I’m just glad I allowed myself to move and sway and get to the place I was meant to be.”

Now, with his UNCG MFA in hand, he is fired up to join the faculty of Kennesaw State University. There he will continue merging dance and film and helping more people discover the beauty in dance.

“I feel like I’ve just gotten started.”