Most people see only the obvious at 442 Gorrell Street – a handsome, two-story frame house accented with lime green trim and encircled by a low wall of rough-hewn Mount Airy granite. Torren Gatson, an assistant professor of history, sees more. When he lays eyes on Greensboro’s historic Magnolia House, he sees “a community vessel.”

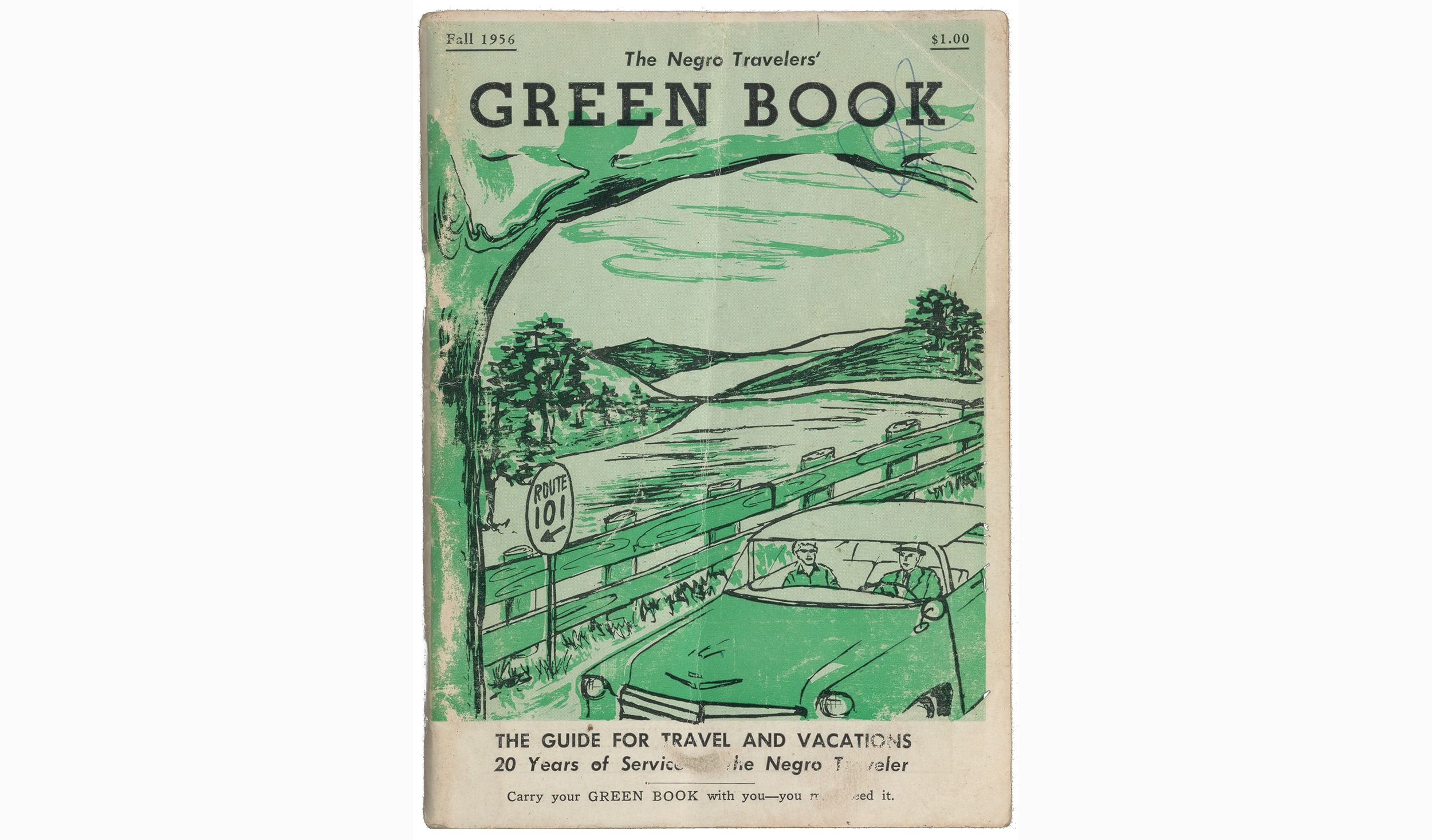

As the Magnolia House Motel from the late 1940s through the 1970s, the property was a safe haven for African American travelers in the Jim Crow era. The Green Book Motorist Guide, the resource for Black travelers recently made famous by Hollywood, listed it in several editions.

Here, close by Bennett College and N.C. A&T State University, the author James Baldwin stayed the night. So did Satchel Paige, Ike and Tina Turner, and Louis Armstrong, who is said to have had a fondness for the innkeeper’s ham biscuits.

Dr. Gatson, in addition to his position in the academy, is a public historian. He revels in engaging with the community to learn the people’s stories, history in the first person.

For instance, there’s the kid who remembers riding his bike past the Magnolia House and seeing James Brown hanging out and playing with the neighborhood children. That kid was Samuel Pass, whose powerful childhood memories led him, as an adult, to buy the property and rescue it.

Today his daughter, Natalie Pass-Miller, is interim director of the nonprofit established to restore and preserve the property and celebrate its service to the African American traveling public. Equally significant is its role as a staging area for social action and the civil rights movement. It’s this latter function that gets the public historian most fired up.

The Magnolia House, Gatson explains, played an elemental role in “the fight for civil rights” in Greensboro and Guilford County. It was a “bastion of culture for African Americans,” he says, where Black people were welcome in the days before integration and racially mixed business and social functions. Owners Arthur and Louise Gist, who bought the 5,000-square-foot structure in 1949, opened the facility to meetings of the NAACP and other progressive organizations.

Image 1: Gatson and his graduate student collaborators examine archival photos with Natalie Pass-Miller (third from left) at the Magnolia House. 2: Students spent the day collecting memories and photos from older local residents at the house and a nearby library. Hands-on, community-engaged work is a hallmark of the Department of History’s master’s in museum studies program. 3: The Fall 1956 Green Book. Photos predate the COVID-19 pandemic. See more on UNCG Research Flickr.

ON THE PORCH

The front porch of a Southern home BA/C – before the advent of air conditioning – was as necessary for livability as a roof and window screens. This was true regardless of race or income. Useful in all seasons, the porch in summer was a place of cool respite for Black and White, rich and poor.

But the porch was particularly important, Gatson says, for those living in shotgun houses, some of the most modest Southern homes.

He and Dr. Asha Kutty, his colleague in UNCG’s Interior Architecture Department, are studying porches in a shotgun house community in Wilson, North Carolina. As late as 1988, the East Wilson Historic District had more than 300 of those houses. Most were built in the first four decades of the 20th century. Today the historically African American neighborhood has fewer than 90.

Five belong to Wilson native and UNCG graduate student Monica Therisa Davis. She and a partner are restoring them as tiny houses. Once an economic necessity, compact homes are now trendy.

Gatson and Kutty will collect oral histories from current and former residents to gain an understanding of what transpired on the porch, a transition zone between the public street and the private interior, and what that meant.

“The porch evolved to serve as a catalyst, a spearhead for community and culture,” Gatson says.

The work combines two of Gatson’s passions, public history and historic preservation, and he’s delighted to be working with Kutty. The pairing of a historian and an architect to explore this aspect of African American culture, he says, should result in “some truly unique work and rich perspective.”

“Just the fact that the Congress of Racial Equality and the NAACP held planning, strategy, and logistical sessions at the Magnolia House,” Gatson says, firmly establishes its place in history. The facility also hosted business meetings. Black Veterans of Foreign Wars met there, as did a Black Women’s Democratic Club and other community groups.

“So, while it’s a motel and a center for civil rights, we’re also saying it’s a community vessel.”

The multi-layered history reflects a family invested in their community. Arthur Gist was a veteran. Ann, the couple’s daughter, and another woman made headlines in June 1957 when they attempted to visit Greensboro’s Whites-only, city-owned Lindley Park Pool.

Arthur and Louise’s sons, Herman and Buddy, carved their own niches in the city’s political and cultural history. Herman represented Guilford County in the General Assembly for more than a decade before his death in 1994. The late Buddy Gist’s friendship with the jazz great Miles Davis led to UNCG naming its jazz studies program for the prolific artist.

Preserving historic sites and identifying artifacts of material culture infuse Gatson’s work, on and off campus. In the classroom or in the field, he thrives on “community-engaged collaborative efforts, mixed with scholarship to produce impactful products.” The deep dive into the Magnolia House gives his students, pursuing master’s degrees in museum studies, the hands-on experience that is essential to their becoming public history practitioners.

Angela Thorpe, director of the North Carolina African American Heritage Commission, says the relationship between Gatson and the Magnolia House “can be a model for preserving other African American heritage assets.” Thorpe, too, has strong connections to UNCG, where she earned her master’s degree in history. “It’s an honor,” she says, “that the Magnolia House has been able to connect deeply with Dr. Gatson to do this critical historic preservation work.”

Image 1: Melissa Knapp, who graduated from UNCG’s museum studies program last spring, is the new site manager at (2) the historic house. See more on UNCG Research Flickr.

Credit Due

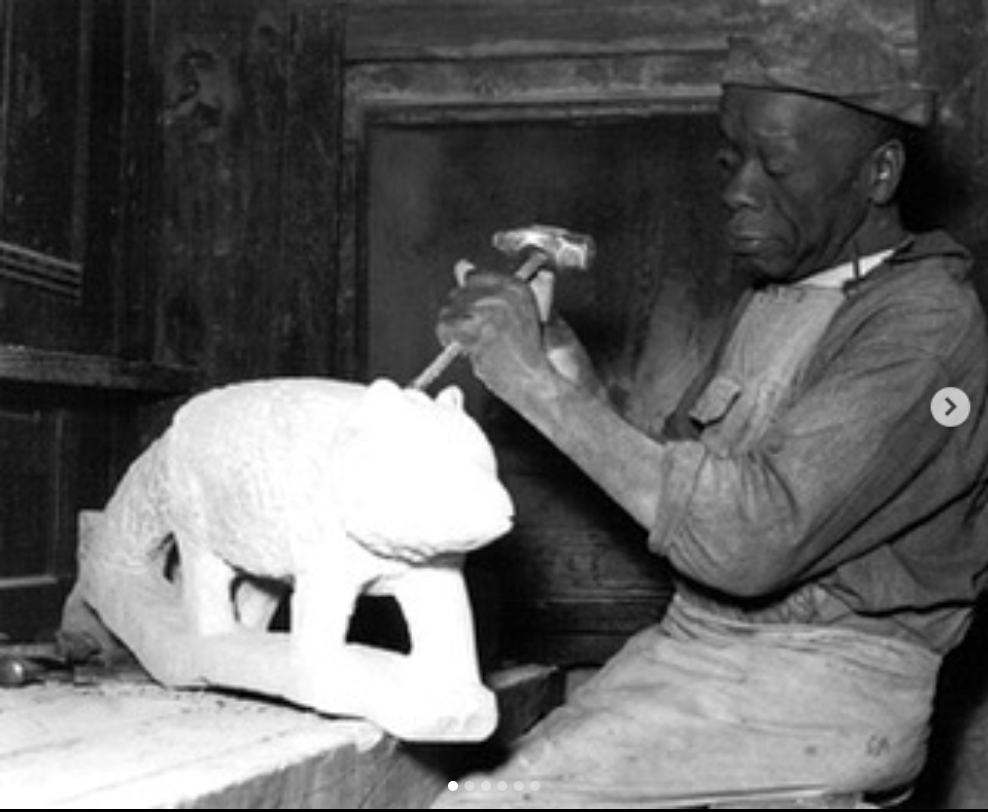

From 1619 onward, they constructed exquisite furniture, sewed fine garments, forged iron, worked leather and tin, and built seagoing vessels in the Southern states. Free or enslaved, Black craftspeople were highly regarded for the quality of their handiwork.

Examples of the artisans’ creations that survive today – such as furniture by Thomas Day, the free Black North Carolina craftsman – are prized by museums and collectors. But Day, who remains well-known 150 years after his death, is an exception among Black craftspeople of that era. Far too many of his peers remain largely unknown.

The Black Craftspeople Digital Archive, or BCDA, seeks to change that. Gatson is co-director of BCDA. The initiative, which seeks to identify and celebrate Black craftspeople of the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, was founded by his colleague Dr. Tiffany Momon, a public historian currently at Sewanee, the University of the South.

In June, BCDA’s Instagram account grew from around 400 followers to nearly 20,000 in a matter of weeks, thanks in part to mentions on some highly trafficked websites. The surge, Gatson says, was a complete shock.” This September, he and Momon launched the BCDA website.

“We know the South was built off of the hands of labor,” Gatson says. “But those skilled craftspeople haven’t been given the full weight and magnitude of attention that is warranted. I’m really honored to work on a project like this.”