APPLIED POTENTIAL

Research helps catalyze a first-gen student’s future

APPLIED POTENTIAL

Research helps catalyze first-gen student’s future

Even during his first year at UNCG, Marcos Tapia had heard that doing research as an undergraduate could boost his chances of success after graduation. But he had no idea how to get started.

UNCG’s First Year Experience 101 – a class that helps students succeed in college – helped him bridge the gap. Tapia, who has always excelled in chemistry and had chosen it as his major, was assigned to do an informational interview with someone in his field.

He chose Dr. Shabnam Hematian, a Bernard-Glickman Dean’s Professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry. Tapia was drawn to her background — the bioinorganic chemist is from Iran and learned to navigate American higher education without the benefit of guidance from family with experience in that system. He was also interested in her work’s focus on environmentally friendly technologies.

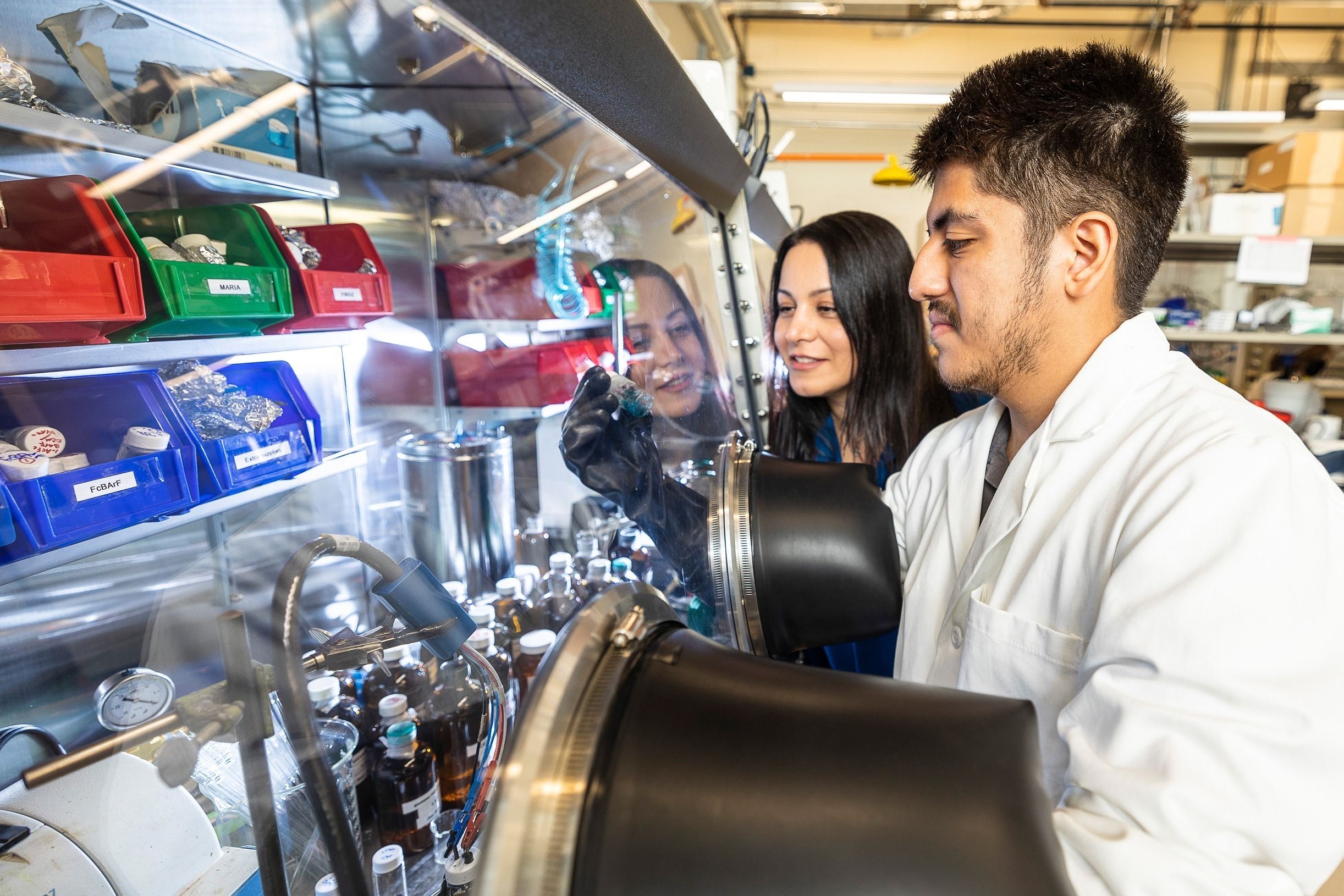

During the interview, Tapia learned how Hematian got started in research and asked her how he could get involved. Hematian recognized Tapia’s drive immediately, and within a few weeks she had invited him to work in her lab.

“I could tell he was invested,” she says. “In December – during the holidays – he finished all of his safety training and the other things he had to do before starting work in the lab.”

Since then, Tapia has become a near daily presence in Hematian’s lab.

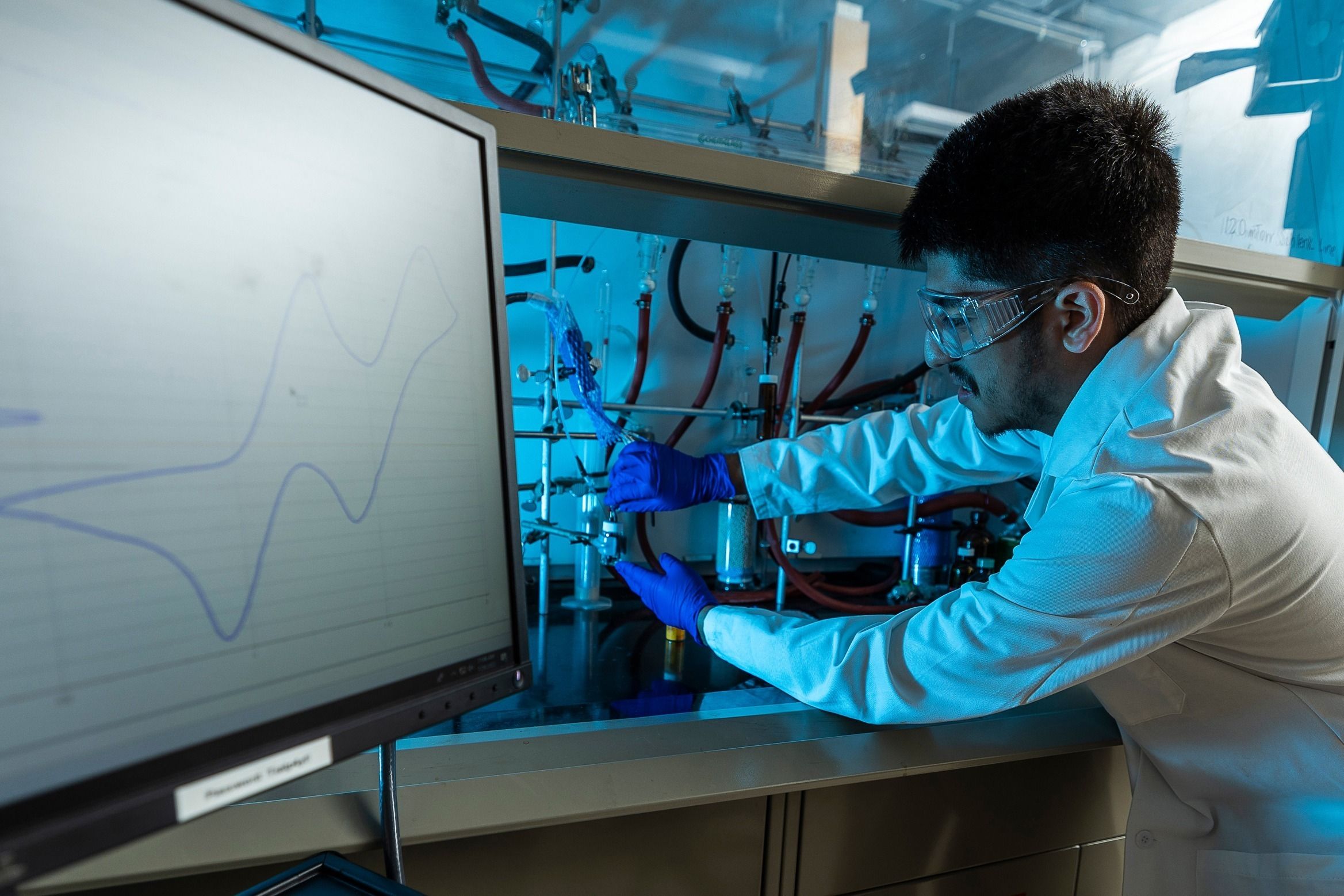

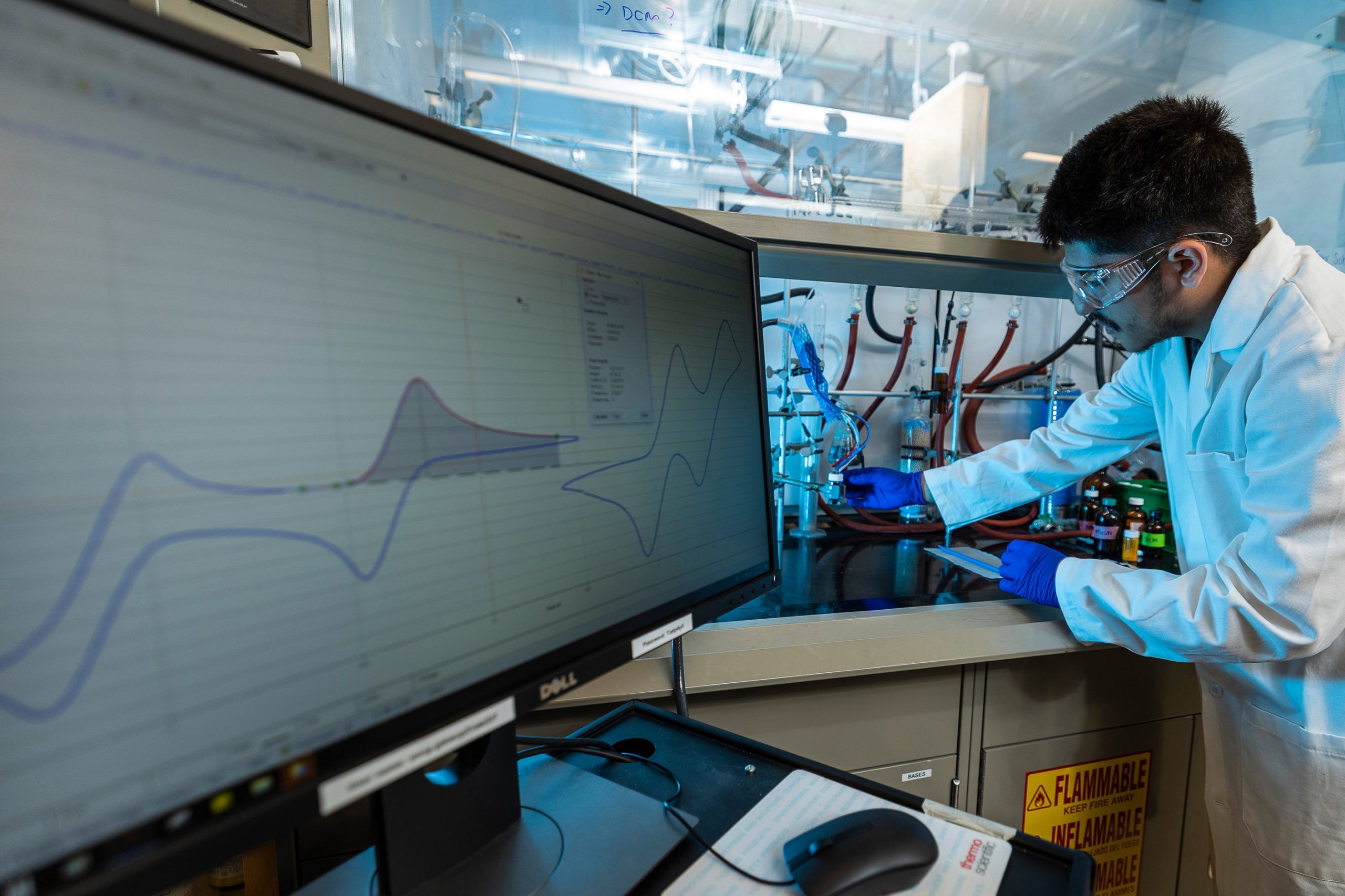

He’s also carved out his own area of expertise: doing experiments in electrochemistry using cyclic voltammetry.

First-gen undergraduate Marcos Tapia dove into research at UNCG. Now, as only a sophomore, he’s already co-authored a scientific article and mastered an in-demand electrochemistry technique. The experience, he says, has opened his eyes to new career possibilities.

In cyclic voltammetry, chemists measure the current produced by a substance under different voltages, giving them insight into how that substance accepts or loses electrons. It’s valuable for Hematian’s research into how electrons flow in certain materials and chemical reactions, which has the potential to make a wide range of technologies cheaper, more efficient, and environmentally friendly.

Learning the skill also provides Tapia with a skill that’s marketable. “Just by knowing that technique you can go get a job,” Hematian says. “For example, electrochemistry is foundational to battery science.”

This summer, Tapia attended a three-day cyclic voltammetry bootcamp as the youngest attendee and one of only two undergraduates.

“Marcos was one of the most engaged researchers,” says UNC Professor Jillian L. Dempsey, who ran the bootcamp. “He asked deep, probing questions about electrochemistry and the associated theory, a true testament to how deeply engaged he is with his own research project.”

Photos: Tapia in the lab working with his mentor Dr. Hematian and a potentiostat, which he uses for cyclic voltammetry experiments

In Tapia’s current work in the Hematian lab, the focus is on understanding how oxygen atoms can be added to a material, and how reversible that process is. As a freshman, he applied for, and won, funding from UNCG’s Undergraduate Research, Scholarship, and Creativity Office to support a research project on oxygen chemistry and copper.

Now, as a sophomore, he has his first publication, co-authored with Hematian and other researchers in her lab.

“Being in a research group actually makes you think about what you are doing” Tapia says. “We do these weekly presentations, and we have to take our data and actually present.”

The lab’s training has prepared him to present his research at conferences this fall, including the Southeastern Regional Meeting of the American Chemical Society in Puerto Rico.

He’s also thinking about life after he earns his bachelor’s degree. He has dreamed of becoming a doctor but graduate school in chemistry is another option to weigh.

“I’m thinking more about my future – undergraduate research has really helped me out with that because I get to talk to people with PhDs, master’s degrees,” he says.

“I get to interact with a community of science that I’ve never been exposed to as a first-generation student.”