Mediating the Housing Crisis

Renée Norris, eviction mediation program coordinator for UNCG’s Center for Housing and Community Studies, says housing is a human right.

“Everyone who chooses should be able to have a place, however small or humble, that they can go and say, ‘I’m home. I’m safe.’”

But as a researcher and lawyer focused on housing issues, she knows things are not that simple. Rising rents and interest rates price many out of the market. There’s a lack of affordable housing, and many existing units are in sometimes-dangerous states of disrepair.

The Center for Housing and Community Studies, or CHCS, conducts research and community-informed interventions to tackle thorny problems exactly like these. Work ranges from a recent affordable-housing study in Baton Rouge to legal-needs assessments for low-income residents in South Carolina and North Carolina, to an affordable housing plan for Gastonia.

Norris’s Eviction Mediation Program focuses on Guilford County.

As recently as 2016, Greensboro had the seventh-highest eviction rate in the country. According to the North Carolina Housing Coalition, 50% of renters in Guilford County had trouble affording their homes in 2025.

Evictions impact renters and property owners and disrupt entire neighborhoods, says Norris.

For example, a recent Legal Services Corporation study determined that eviction proceedings are rarely beneficial for landlords, costing $2,500–$8,000 per case and resulting in fewer than 10% collecting owed back rent.

Through education, advocacy, and intervention, the CHCS eviction mediation program – a collaboration between UNCG and Legal Aid of North Carolina – benefits the entire community.

Story highlights

UNCG’s Center for Housing and Community Studies tackles the housing crisis through its Eviction Mediation Program, in collaboration with Legal Aid of North Carolina.

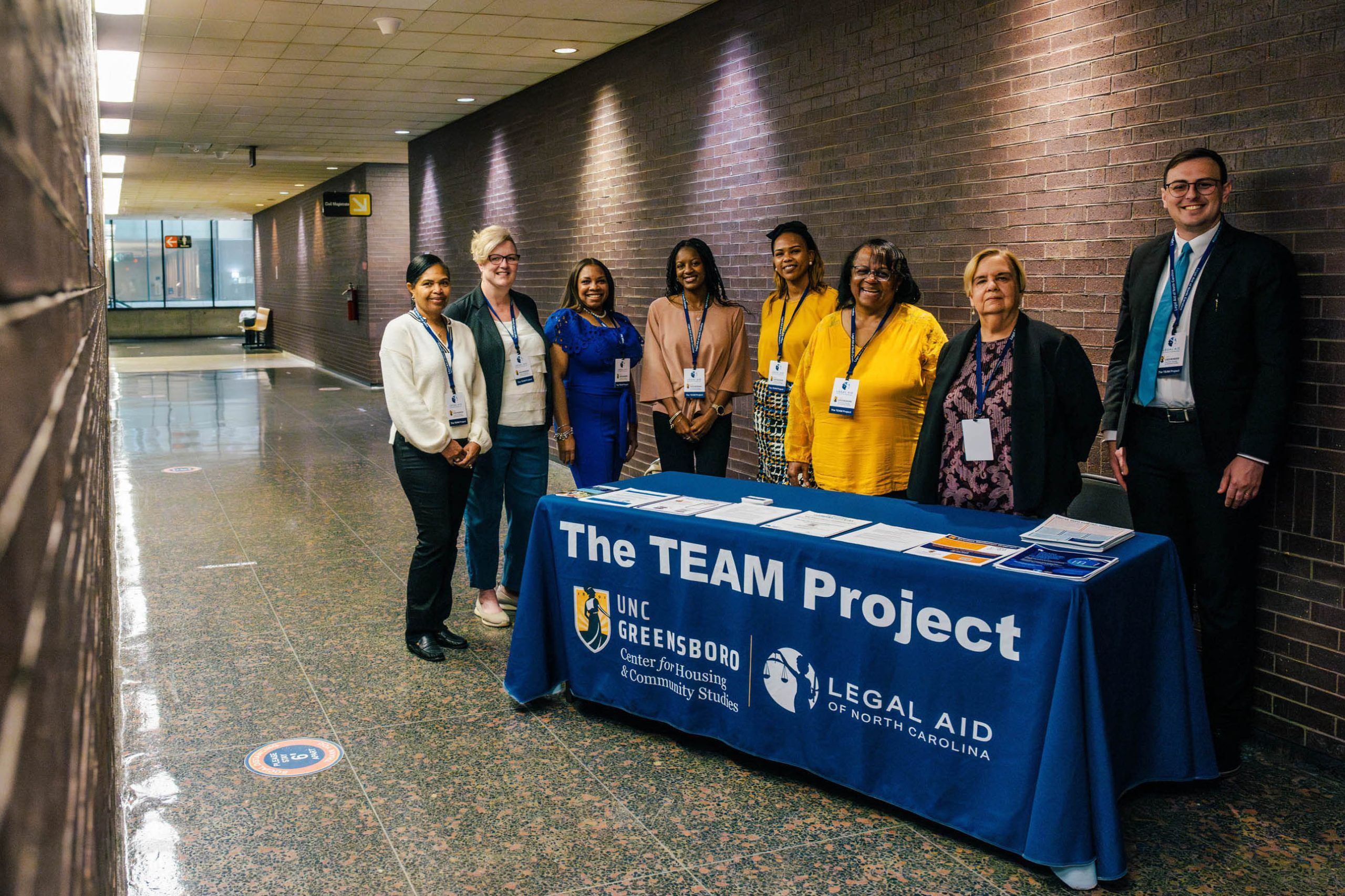

(1,3) The CHCS and Legal Aid teams work with tenants twice a week in the Guilford County Courthouse in Greensboro. (2,4) CHCS Eviction Mediation Project team outside the courthouse in Greensboro’s Government Plaza complex. (In photo 1, Norris is third from right, Cheema, far right, and Tillman, far left.)

Real-world impact

“We partner together twice a week in the Greensboro courthouse and twice a week in the High Point courthouse,” explains Michael Cheema, a Legal Aid attorney. “Tenants can come to our table and receive mediation services, get connected with affordable housing, or get matched with a lawyer.”

Across three years, project personnel have worked with 3,771 tenants at courthouse clinic days and 2,985 clients outside of clinic days.

“Sometimes we will see someone in court because they owe $1,000 or $2,000 – mostly due to a job issue, either reduced work hours or losing their job,” Norris says. “By the time they get the new job, they’re already a month or two behind. Or it’s a temporary health issue.”

Rental assistance and mediation make a big difference in these cases.

Cheema has been deeply moved by the program’s impact.

“So many of my clients describe facing eviction proceedings in court as one of the most humiliating experiences of their lives – or scariest. The center does a lot of work to stop things from having to go to court, so tenants don’t have to go through that.”

For example, CHCS Landlord Outreach Specialist Tara Tillman uses her real estate background to connect with landlords. “Our goal is to find out what they’re thinking and explain mediation and the voucher system, and how that can benefit them,” Norris says. “It’s a hard climb, but she speaks the language.”

The center’s list of housing vacancies in Guilford County is also more accurate and complete than the one posted by NC Housing Search.

A rising tide

During the early years of COVID, Norris says, evictions declined because Greensboro and Guilford County won American Rescue Plan Act Emergency Rental Assistance program grants that helped people stay housed.

Pandemic-related funds mostly dried up in 2023, but the problem of eviction remains. In recent years, Norris has seen rents rise and other troubling trends.

She says fewer landlords are accepting federal Section 8 rental-assistance vouchers from low-income renters. Meanwhile, rental-pricing software tools can push rent to upper limits, while aggressive bargaining and cash purchases by investors make homeownership less accessible. The rise of corporate ownership of rental properties further stresses the system.

“They don’t give property managers a lot of leeway,” Norris adds. If a corporate policy says no partial payments, for example, mediation is out the window. “They don’t have the sense of community, or the sense of investment in our community.”

Guilford County’s homeless population largely tracks with the rise and fall of the rental-assistance programs.

An annual point-in-time count shows a high of 721 people experiencing homelessness in Guilford County in 2016 – 129 of them under 18. The total number reduced to 452 in 2023 but rebounded to 665 in 2024.

Homelessness, Norris says, becomes a community problem when people are forced to live on the street.

Businesses that rely on employees getting to work, on consumers with dependable income, and on safe streets to engage in commerce have as much of a stake in this as local government, neighborhoods, and community organizations do.

“We’re never going to solve anything by thinking of the other side as the enemy,” Norris says.

“We need the landlords. And they need the tenants. We need to realize that we all have valid points of view, and that none of us want people to live on the street.”