Bringing Down Barriers to Breastfeeding

It’s no secret to most parents that breastfeeding is tough. But popular culture tends to present this critical activity as effortless and intuitive – setting some parents up for a surprise when they face barriers, including lack of time, support, and confidence, as well as physical limitations.

Dr. Jasmine DeJesus, an associate professor in psychology, recently experienced difficulties breastfeeding her first child. “I just have one experience with one kid, but it’s really opened my mind up: What are the bigger range of experiences?” she asks.

Now, DeJesus and Dr. Jigna Dharod, professor in nutrition, are leading a $784,369 NIH-funded trial to reduce some of the barriers Latine parents face when breastfeeding.

It’s a needed project with trickle-down impacts that can help address the high obesity rate among U.S. Latine children. Almost half of the adult U.S. Latino population is obese, and infant nutrition serves as the foundation for lifelong health.

Formula feeding is linked to rapid weight gain in infants, which is in turn linked to childhood obesity and to lifelong obesity, the researchers say.

In a 2023 study of low-income families, Dharod and DeJesus found that infants fed only formula had three times higher risk for rapid weight gain.

“Infancy is a very important life stage. It’s a highly developmental phase, and it’s a phase of immense opportunities,” Dharod says. “At the same time, any vulnerabilities during this phase can have a lifelong impact.”

In their latest investigation, the researchers want to know whether peer counselors and financial compensation can help increase parents’ confidence in continuing with breastfeeding.

The duo bring decades of complementary, cross-disciplinary expertise to a topic they both found somewhat unexpectedly.

DeJesus’s love of food and fascination with culture led her to research on child-parent interactions and social learning with food. “My dad is Puerto Rican. My mom is Jewish, and I grew up here in the U.S.,” DeJesus says. “Even as a little kid, I knew that food and language were things that marked our family’s cultural background.”

Over 8,000 miles away from DeJesus, Dharod grew up in India and observed firsthand how access to food can lift people out of poverty. She decided to pursue research on food insecurity. During her doctoral studies, she became curious about maternal and child nutrition and health equity. “Breastfeeding ensures food security for the infant, especially for the first six months,” she says.

What’s for dinner, baby?

UNCG researchers bring evidence-based strategies to support parents and babies, both locally and globally.

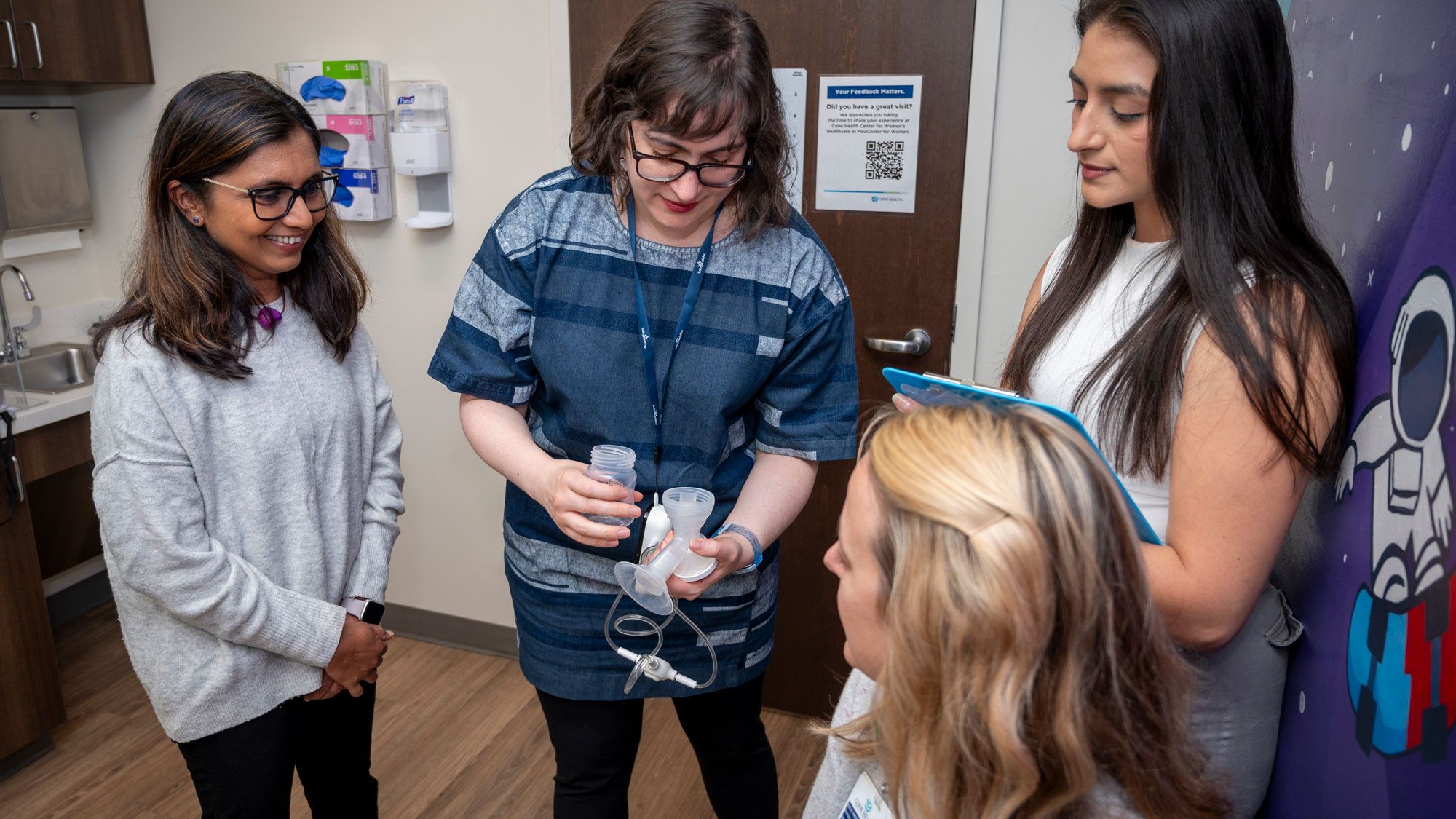

Photos: Dharod, DeJesus, and grad student Selena Villa work with Dr. Marjorie Jenkins and Julie Wenzel at the Cone Health MedCenter for Women, where study participants are being recruited. Mothers enrolled in the treatment group will receive a combination of cash and a pump or cash, depending on their preference. Trained peer counselors will then provide house visits and support tailored to mothers’ needs, preferences, and language.

Removing obstacles

Dharod and DeJesus say many Latina mothers hope to breastfeed but end up quitting before they reach their goals.

“Previous literature shows that many times a mother’s intentions are to continue with breastfeeding, but they stop,” Dharod says. “One of the key predictors of this is low self-efficacy, or confidence, in their ability to breastfeed.”

Finances and government policies can also play a role. Through WIC – the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children program – low-income parents can opt into different packages for breastfeeding or formula feeding.

“The monetary value of WIC’s breastfeeding package is much lower than the formula assistance package,” Dharod says. “With formula assistance, families receive a few hundred dollars’ worth of infant formula. Exclusively breastfeeding mothers receive supplemental foods worth about $75.”

DeJesus and Dharod designed their multicomponent trial to provide needed support to parents looking to breastfeed more or for a longer duration.

“What’s most novel about our approach is to have culturally matched and bilingual peer counselors,” says DeJesus. “A peer counselor, especially one who speaks the same language as participants, can provide knowledge that can be helpful in navigating challenges.”

The researchers will compare whether the mothers with this support have higher rates of exclusive breastfeeding and self-efficacy. They will also track infants’ weight gain and obesity risk across the first six months of their lives. This project is expected to run until 2027.

Community connections

Dharod has led two previous NIH-funded projects involving breastfeeding. In the first, her team found housing insecurity is linked to early discontinuation of breastfeeding. The second explores how stress can play a role in breastfeeding behaviors in low-income households.

“It’s possible because we have partnerships in place to reach hard-to-reach populations,” Dharod says.

Dr. Marjorie Jenkins, Cone Health’s system-wide director of nursing research, works closely with the UNCG team.

“It’s amazing to see how our investment in one small grant led to the next. We can provide our analysis, of course, but what we do with our results matters far more,” Jenkins says. “Through this research, we’re ultimately changing lives as we discover new ways to make a difference in the communities we serve.”

Taking a preventative approach to health is also central to the UNCG School of Health and Human Sciences mission. Dharod and DeJesus say they feel the university’s alignment with their work.

“There’s a lot of support for community engaged research at UNCG,” DeJesus says.

“I think in other places people feel more stifled – like it’d be more of a risk for them to take on a project like this because their university may not value all the work it takes to cultivate these connections, but we have had this opportunity.”

In a 2023 study of low-income families with infants, Dharod and DeJesus linked formula feeding with overfeeding. Specific guidelines on formula feeding and education are critical, they say.

Student Opportunities

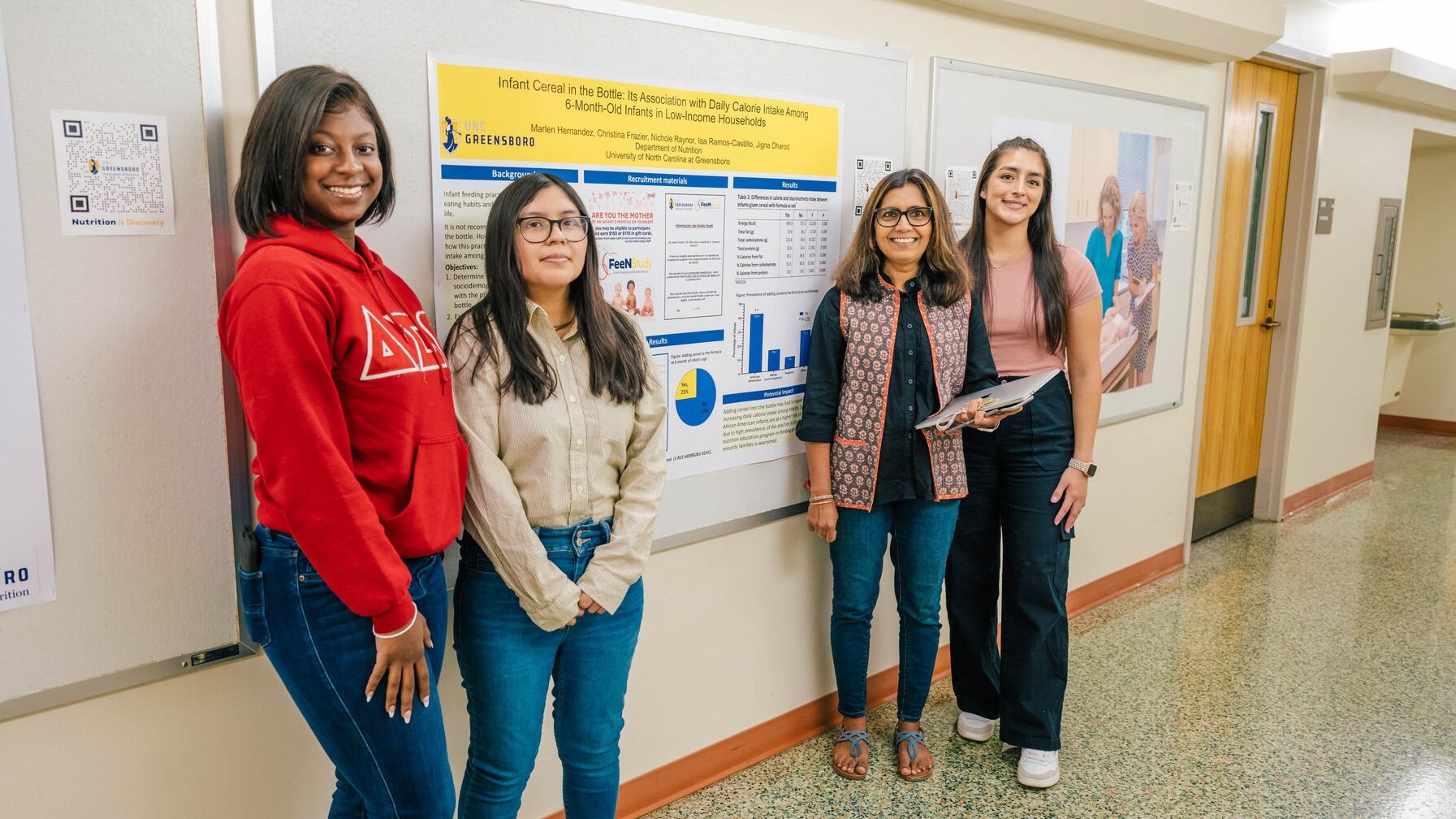

Another strength: dedicated students motivated to serve their community.

Spanish-speaking undergraduate and graduate students are part of the research team, translating materials and recruiting mothers.

Selena Villa, a master’s student in nutrition, has worked with Dharod since she was a sophomore at UNCG.

“I didn’t know you could do research like this as an undergraduate, and I was just shocked,” Villas says. “I really appreciated her believing in me.”

Dharod and DeJesus are equally appreciative of the student researchers.

“They can be cultural brokers and help us bridge that gap and build trust,” Dharod says. “It’s a win-win situation for the research, the student, the community, and UNCG.”

Dharod and DeJesus say they hope to build this work into a future larger-scale trial.

“In addition to learning something scientifically, we also have the power to actually help people, and that’s something that’s really exciting to me,” DeJesus says.