Donor Milk for Preterm Infants

Donated human breast milk, or donor milk, is in high demand. For babies born prematurely to a parent unable to provide breast milk, it can even be a matter of life and death.

These preterm babies are at a high risk for a potentially fatal gut infection, necrotizing enterocolitis, and being fed breast milk can improve their odds. When parents are not yet able or unable to breastfeed, donor milk can be critical.

But, contrary to popular belief, not all breast milk is the same.

“There’s millions of very vulnerable babies being fed donor milk, but we don’t know what it is nutritionally,” says UNCG associate professor of nutrition Maryanne Perrin. “It’s not a consistent product, and we don’t understand the sources of variation.”

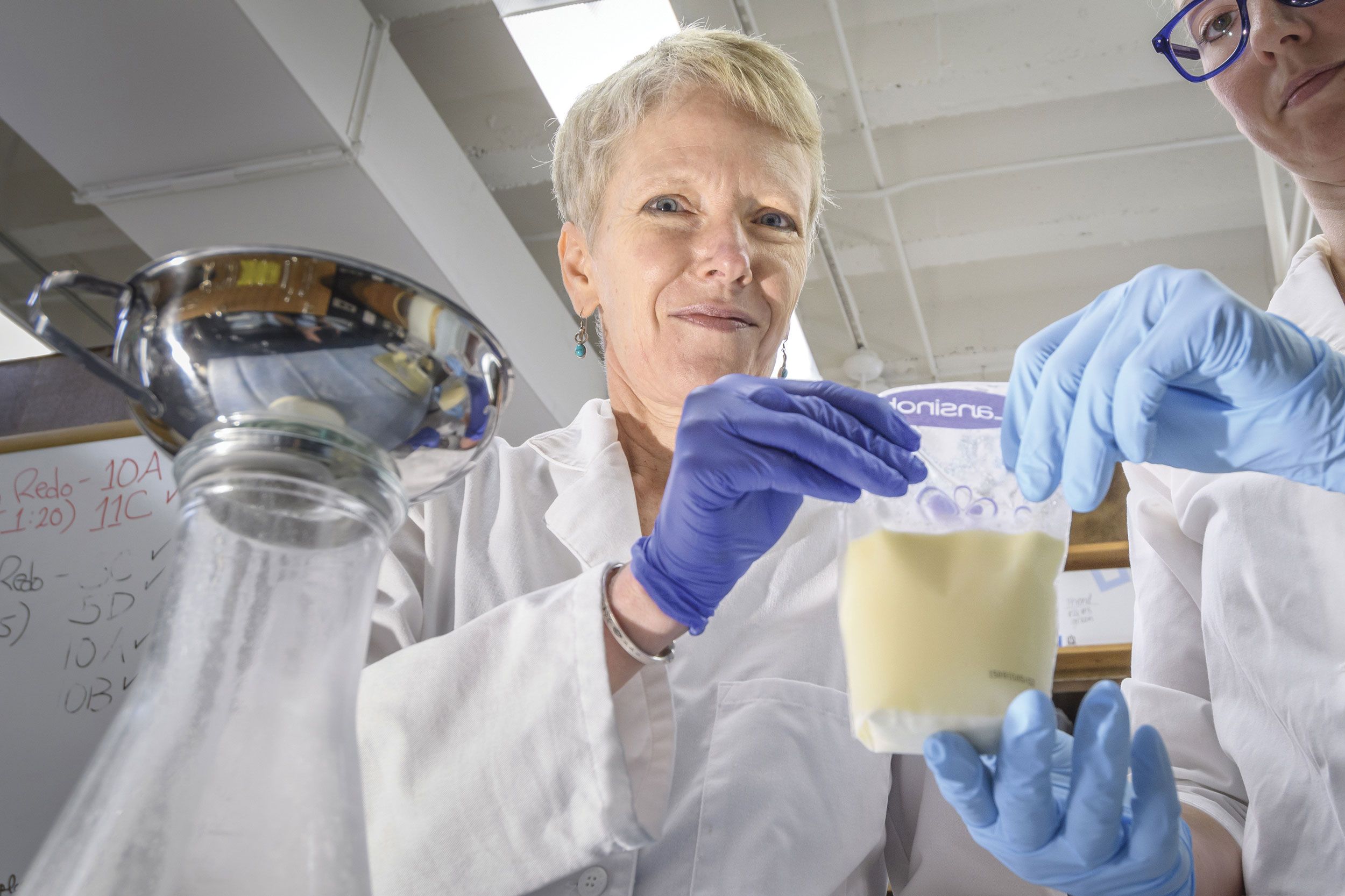

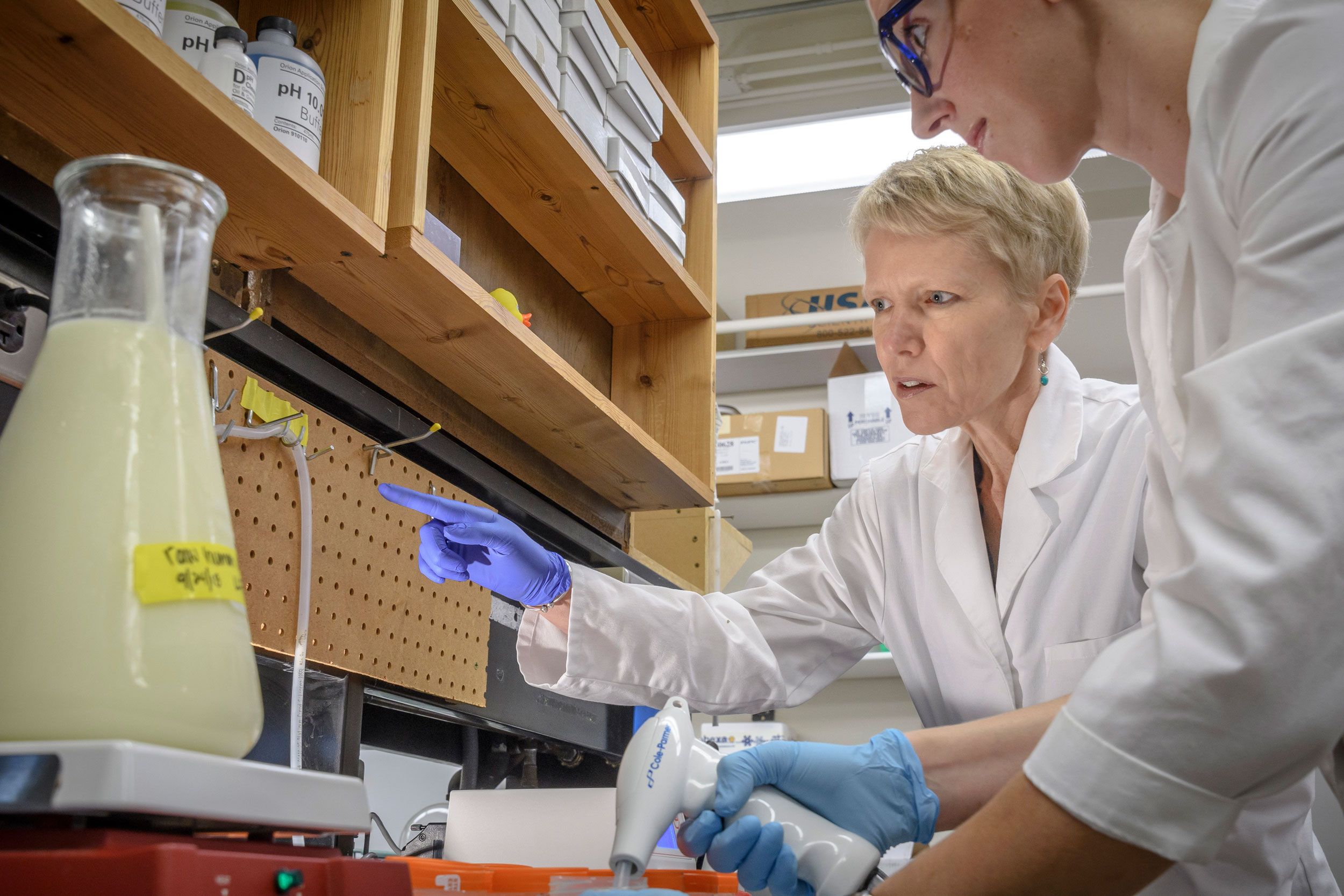

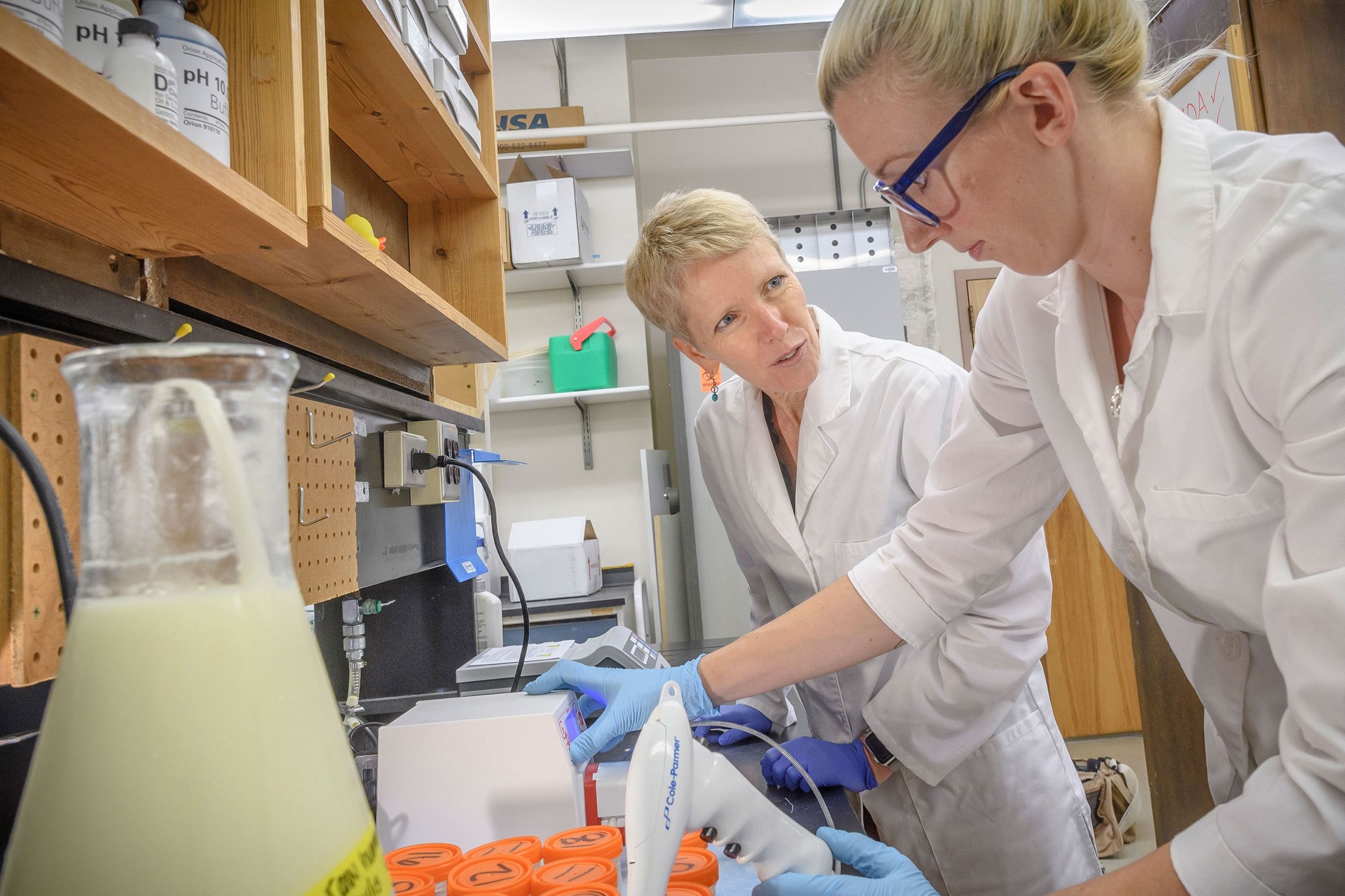

In Perrin’s laboratory, she’s working to unravel these differences in donor milk: a problem she’s well-suited, and arguably the first, to address. Perrin worked as an industrial engineer for years before going back to school for her doctorate in nutrition after having children.

“This is a really nice combination of nutrition science, but it’s also the industrial engineering processes of making donor milk,” Perrin says. “I never imagined finding a field that brought together the first and second halves of my very different careers.”

What’s for dinner, baby?

UNCG researchers bring evidence-based strategies to support parents and babies, both locally and globally.

Perrin and her students explore a wide range of factors potentially impacting breast milk composition, such as the donor’s stage of lactation and their diet.

Discrepancies in donor milk

If you thought all donor milk is the same, you’re not alone. Perrin says it’s a common misconception, even among medical professionals.

While some aspects of breast milk are similar – all have a high level of lactose – other nutrients vary. Mothers’ genetic differences contribute to some of the variations in their breast milk, she says. Timing of the donation may also play a role.

“If you’re an infant and born preterm, we’re pretty sure that your mother’s milk is going to be higher in protein than a mother who gave birth at term,” Perrin says.

After milk is donated, the storage and pasteurization processes can also cause changes to the milk, such as less fat from container transfers and a decrease in some micronutrients, including Vitamin C.

Perrin is currently collecting samples from 600 approved milk donors at 8 different milk banks from around the world, including the U.S., Kenya, Poland, Chile, and Vietnam, to assess nutrients and bioactive factors and compare samples.

The critical work has received $1.4M in funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Her team already has results for over 50 nutrients.

Among their preliminary findings, they have discovered donor milk has greater variation in its micronutrients – the vitamins and minerals – compared to its macronutrients – the fat, lactose, and protein.

Perrin and her team plan to use computer modeling to see how milk banks can reduce this variation during the production process. They plan to wrap up and publish this work in spring.

“This study is important because it is going to establish a very rich reference value for what we can expect the nutrients in donor milk to be. It’s a first step,” Perrin says.

“If we know what’s in donor milk, we can think about how we might change our feeding protocol – such as adding fortifiers to donor milk, to better meet premature infants’ nutritional needs.”

Donor milk safety worldwide

Donated milk is collected by milk banks for processing and distribution. Perrin is active in policy efforts to promote safe practices in donor milk banking.

In 2022, she was tapped to be one of 16 members of the World Health Organization’s Guideline Development Group for establishing and implementing safe and quality human milk banking systems. Perrin, the only U.S. researcher in the group, serves as its co-chair.

By creating consistent standards for milk banking, the global group is helping ensure babies most in need of donor milk receive it safely.

“This is a population that didn’t exist 30 years ago – babies that were born around 24 weeks didn’t survive,” Perrin says. “There’s so much work to be done.”