In the field

In the field

When Dr. Gideon Wasserberg and his students began collecting chiggers across North Carolina, they didn’t expect to find disease-causing bacteria typically only seen in the Eastern Hemisphere.

But that’s just what they discovered. Their observation of Orientia bacteria in North Carolina chiggers – part of a collaboration with NC State University – was recently published in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The scientists were tracking the statewide prevalence of chiggers, mites that feed on human and animal skin tissue while in their larval stage. They were also assessing what – if any – disease-causing bacteria these parasitic arachnids host.

“We tested for Orientia because it’s really the only known pathogen of medical concern to be vectored by chiggers,” Wasserberg said. “But we did not really expect to find it because scrub typhus, the disease associated with Orientia, is typically seen in south and east Asia and northern Australia.”

Scrub typhus is a potentially lethal disease that can lead to headaches, muscle pain, and mental confusion, and affects approximately 1 million people each year.

The unexpected findings have stirred media interest about potential implications for North Carolinians who spend time outside and may encounter these chiggers.

“We still don’t know if the Orientia we found is capable of causing disease,” Wasserberg says. “This is part of the next phase of our research.”

Story highlights

Biology professor Gideon Wasserberg studies disease-carrying parasites locally and across the world. He recently identified bacteria in NC chiggers that may cause a disease previously unseen in the U.S.

→ chiggers and ticks of NC

→ the deserts of Israel

→ combating Leishmaniasis globally

→ appreciation for nature

Chiggers and ticks of NC

While still unfolding, their findings have the potential to make a big impact – particularly for hikers who hope to avoid insects and arachnids that could make them sick.

Wasserberg led the data collection component of the study, traveling with UNCG graduate students, including study co-author Reuben Garshong, to state parks across North Carolina. The scientists use everyday items to collect the tiny bugs, simply placing a small black tile on the ground and waiting for chiggers to emerge from their hiding spots.

“Chiggers are known to occur near sheltering items like logs, bricks, and rocks in shaded areas,” Wasserberg says. “Once they sense a host, they come crawling out searching for it like little zombies.”

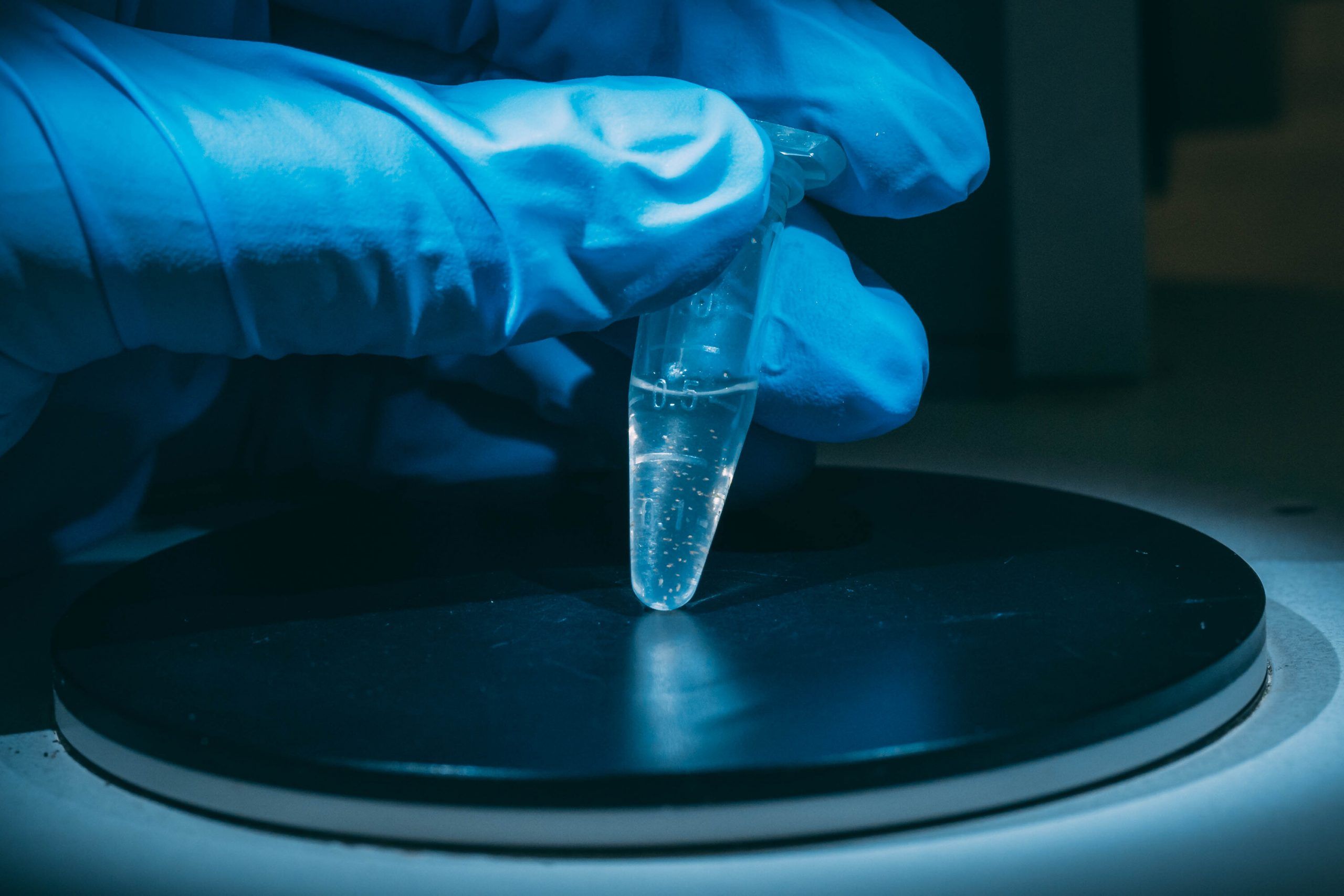

Rather than a host, these chiggers encounter a tile and a scientist, who uses a fine paintbrush dipped in alcohol to transfer the chigger to an alcohol-containing vial.

This relatively simple sampling technique, followed by laboratory analysis at NC State, led to their exciting discovery. Now, Wasserberg and biology master’s student Noah Holland are working to better understand where and when chiggers appear across North Carolina – and where and when they carry Orientia.

Wasserberg is also conducting CDC-funded research in collaboration with the NC Department of Health to track ticks across the state.

“Our findings indicate that blacklegged ticks – some carrying the bacteria that causes Lyme disease – are most prevalent in the northwestern counties of NC,” Wasserberg says. “We also sporadically see them in the Piedmont and coastal regions.”

“The eureka moment of discovery gives me my greatest sense of satisfaction. Helping young scientists develop the tools to make such discoveries, fulfill their potential, and make valuable contributions to society fills me with my greatest sense of pride. My students are like my children.”

📷 Wasserberg collects ticks and chiggers in the field with mentees Reuben Garshong – who graduated with his PhD from UNCG and is now a postdoc at NC State University – and Noah Holland.

Solitude and scientific success

To study insects and arachnids, Wasserberg spends a good deal of time outdoors – a passion he developed in high school at a remote boarding school in the deserts of Israel.

“There’s a meditative solitude in nature,” he says. “It helps you to see things clearly.”

During long hikes as a student, Wasserberg would keep a close eye out for sand flies. A bite from a sand fly infected with a protozoan parasite can cause a disease called Leishmaniasis, commonly characterized by severe skin lesions.

Little did Wasserberg know that the sand flies he was avoiding would become a cornerstone of his career.

Over the past two decades, his research on sand flies and Leishmaniasis prevention has been funded by the National Institutes of Health, Department of Defense, National Science Foundation, and North Carolina Biotechnology Center.

Wasserberg’s work has netted over $2 million in funding, which is not surprising given that Leishmaniasis affects an estimated 1 million people each year in tropical and arid regions of the world. One form can even be fatal if left untreated.

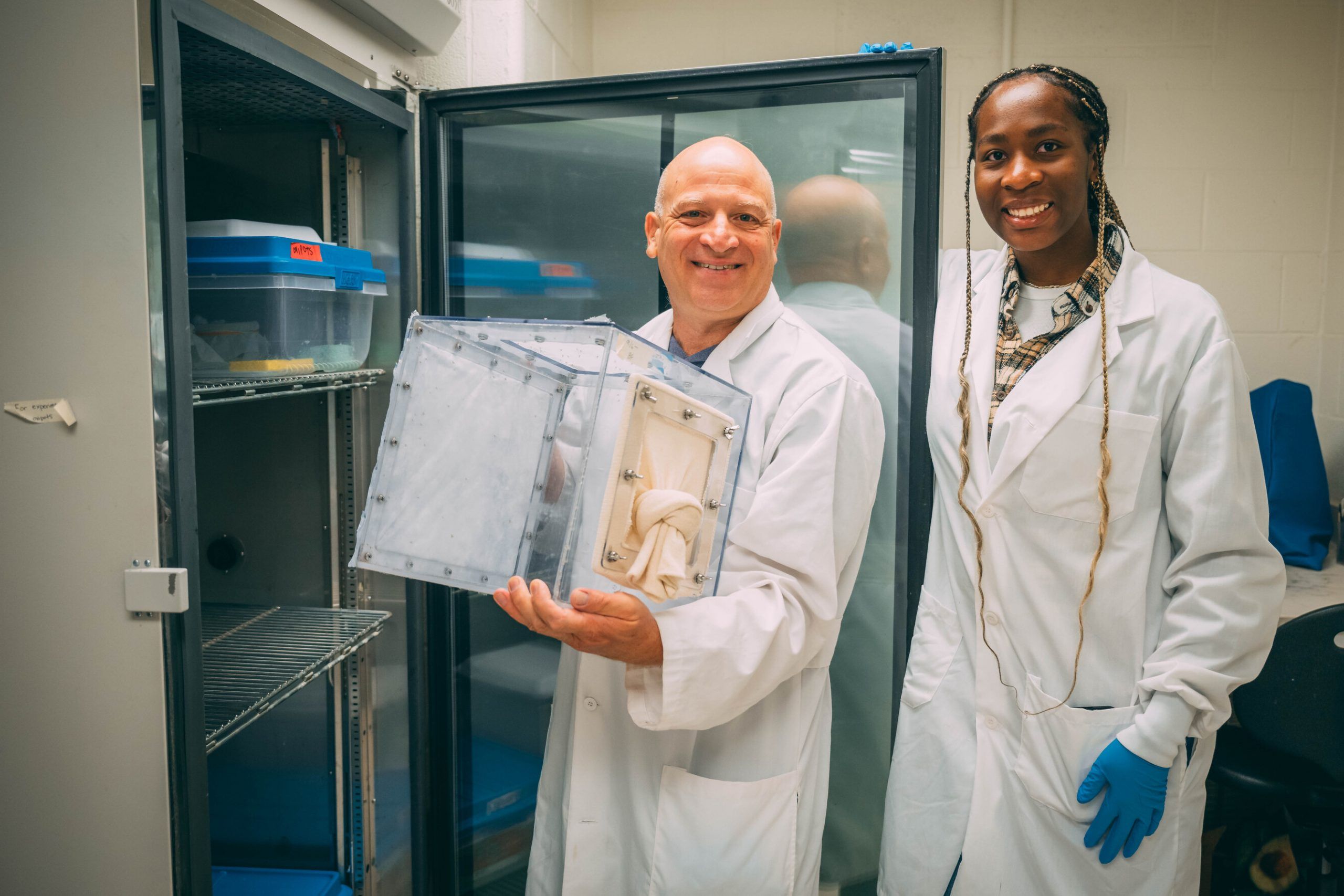

📷 Undergraduate researcher Chelsea Akabueze assists with the maintenance of the sand fly colony, with supervision and training from doctoral student Dannielle Kowacich.

“I was particularly interested in this research because sand flies are actually found in Nigeria, where I’m from,” says Akabueze. “I took Dr. Wasserberg’s class last year, and we learned about how the environment and vectors and hosts interact. Humans affect their environment, and there are consequences from that. I really enjoyed looking at it from that perspective. So I emailed him to ask if I could work in his lab.”

Suppressing sand flies

Studying the ecology of Leishmaniasis and its primary vector, the sand fly, has led Wasserberg to several potential methods to control the disease.

As part of a prestigious NIH R01 project, he and collaborators at NC State have identified chemicals, visual cues, and bacteria sources that entice egg-bearing sandflies to lay their eggs, with the goal of creating attract-and-kill traps.

Sand flies must feed on blood to produce eggs, so egg-bearing – or gravid – sand flies are most likely to carry the Leishmaniasis parasite. “By attracting gravid females to a lethal trap, we can simultaneously impact sand fly population and Leishmaniasis parasite transmission,” Wasserberg explains.

He and collaborators in Israel are also targeting the rodents that sand flies depend on.

A rodent burrow in the desert is a hotbed of sand fly activity, serving as a shelter and a place where females feed on rodent blood and larvae feed on rodent droppings. That’s why the scientists are field testing an insecticide-laced rodent bait.

“It’s a trojan horse approach,” explains Wasserberg. While the insecticide is harmless to the rodent, it’s lethal to the sand flies waiting in the rat’s burrow to feed on rodent blood and feces.

So far, the researchers have observed decreased sand fly numbers in treated burrows and decreased Leishmaniasis infections in treated areas. Now they’re testing the bait in villages in Israel.

“This work will not eradicate Leishmaniasis in the world, but it could be helpful in reducing human exposure in affected areas,” he says.

Little bits of wonder

To advance his research, Wasserberg maintains a sand fly colony in his laboratory here at UNCG. It’s not easy, but Wasserberg says he enjoys working with the fascinating creatures.

His passion is infectious, and his proteges – from the students working with sand flies in the lab, to those tromping through the woods in search of arachnids – are equally enthusiastic.

Holland says he connects with his advisor’s appreciation for nature.

“He, like me, is someone who can just kind of enjoy a little bit of wonder and seeing things you don’t necessarily expect,” Holland says.

During one field work day, Holland and Wasserberg stumbled upon a wild dung beetle trying to roll a dung ball uphill. “We both sat there for maybe 5 or 10 minutes watching and tried to help it get over a stick,” Holland says.

While Wasserberg spends extensive time conducting lab work and writing papers, field work has a special spot in his heart.

“Sometimes I joke that science is an excuse for me to be out in the field,” Wasserberg says. “When you’re in nature, it’s fascinating and raises questions of why things are working the way they do.”