A GROWING EFFORT

A GROWING EFFORT

A three-year-old climbs inside her very own rocket ship. In the process, she gives us data on how to prevent one of the most serious epidemics facing American children.

It’s a fresh approach by a multidisciplinary team of experts at UNC Greensboro who have joined forces to combat childhood obesity.

Obesity affects 14.7 million children and adolescents in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and is associated with some of the leading causes of death worldwide, including death from diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and some forms of cancer.

Dr. Leerkes is principal investigator on the $3 million NIH-funded “iGrowUP” study, which is tracking children from ages three through five – a time in their lives when they begin developing independent self-regulatory behaviors.

The study is an expansion of UNCG’s prestigious $2.8 million iGrow – Infant Growth and Development – study, which followed approximately 300 children from the womb to age two, along with their families, and broke ground as one of the first research studies to simultaneously examine the biological, psychological, and social factors that could raise obesity risk from infancy through toddlerhood.

For the new project, nutrition’s Dr. Lenka Shriver, kinesiology’s Dr. Laurie Wideman and Dr. Jessica Dollar, and human development and family studies’ Leerkes are following many of the same children from the original study, now during the critical time when they start learning how to control their own behavior.

The unprecedentedly detailed dataset around families and the development of healthy – or unhealthy – weights at the earliest stages of life is already producing diverse findings, but, ultimately, the researchers are focused on how they can aid families.

“We could create a toolbox for parents,” says Shriver, “that can be tweaked and individualized based on the child’s characteristics, the environment, and what’s going on within the family.”

Story Highlights

An ambitious child obesity study following kids from womb to toddlerhood expands into the preschool years, with a new $3M NIH grant.

The project’s robust data set is also seeding new studies:

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

An ambitious child obesity study following kids from womb to toddlerhood expands into the preschool years, with a new $3M NIH grant.

The project’s robust data set is also seeding new studies:

Their favorite rocket ship

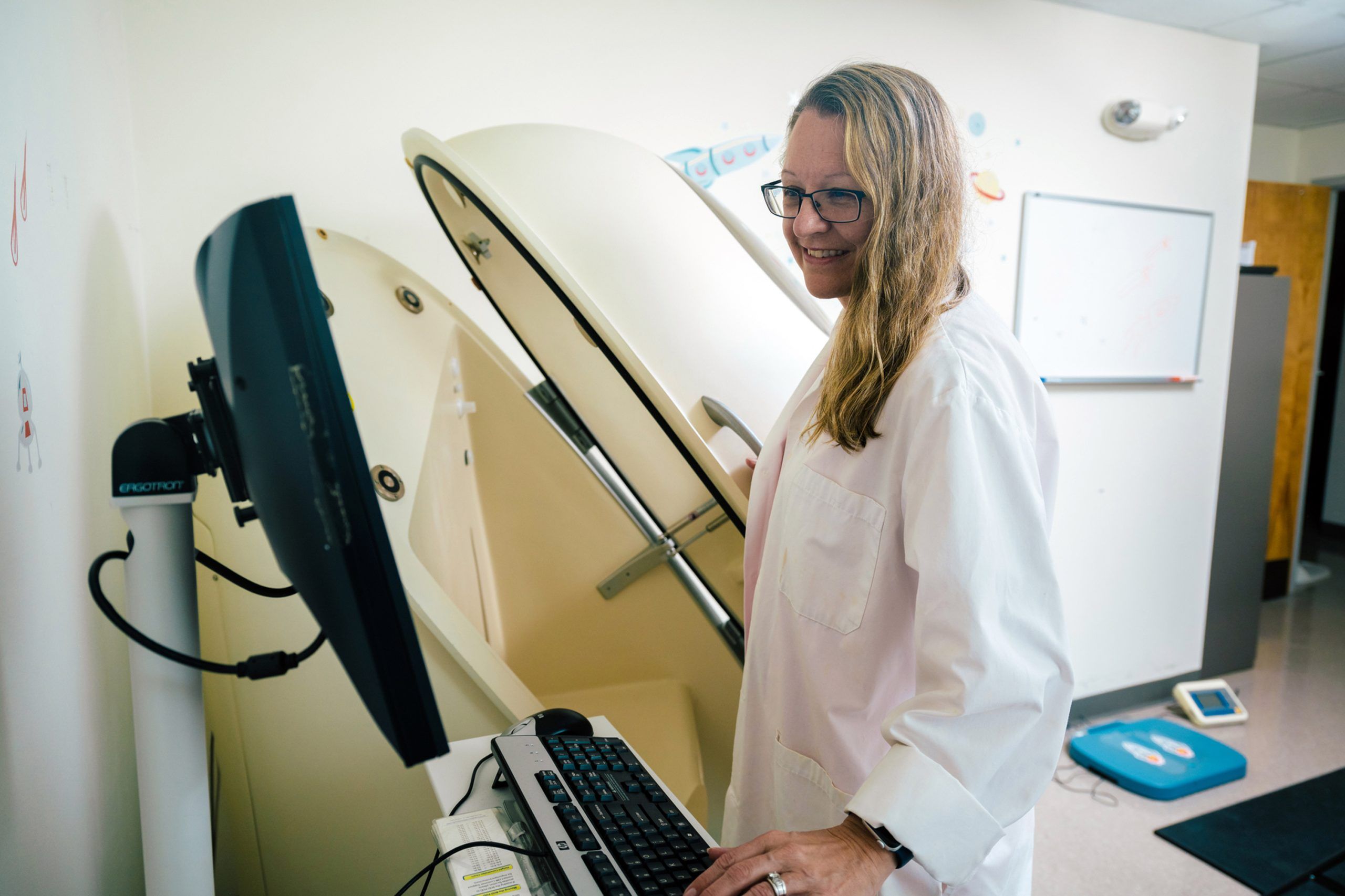

iGrowUP study participants will revisit the iGrow lab in the UNCG Stone Building, where they can record their responses to tasks that involve food and tasks that do not. A device called the Bod Pod will measure their body composition.

“It looks like a big egg,” says Wideman, UNCG’s first Safrit-Ennis Distinguished Professor. “We tell the kids that it’s like a rocket ship. It’s fun, and we make it interactive for them.”

Researchers will also gather information on the children’s social environments, including exercise and what foods are within reach at home. They’ll collect data using surveys, behavioral observations, and accelerometers.

“We’ll have one of the only datasets in the world that has co-assessed parent-child physical activity in kids that young,” Wideman says.

Working with such young research participants is no easy task, but Leerkes says, “We are all mothers ourselves, and we’re familiar with these struggles.”

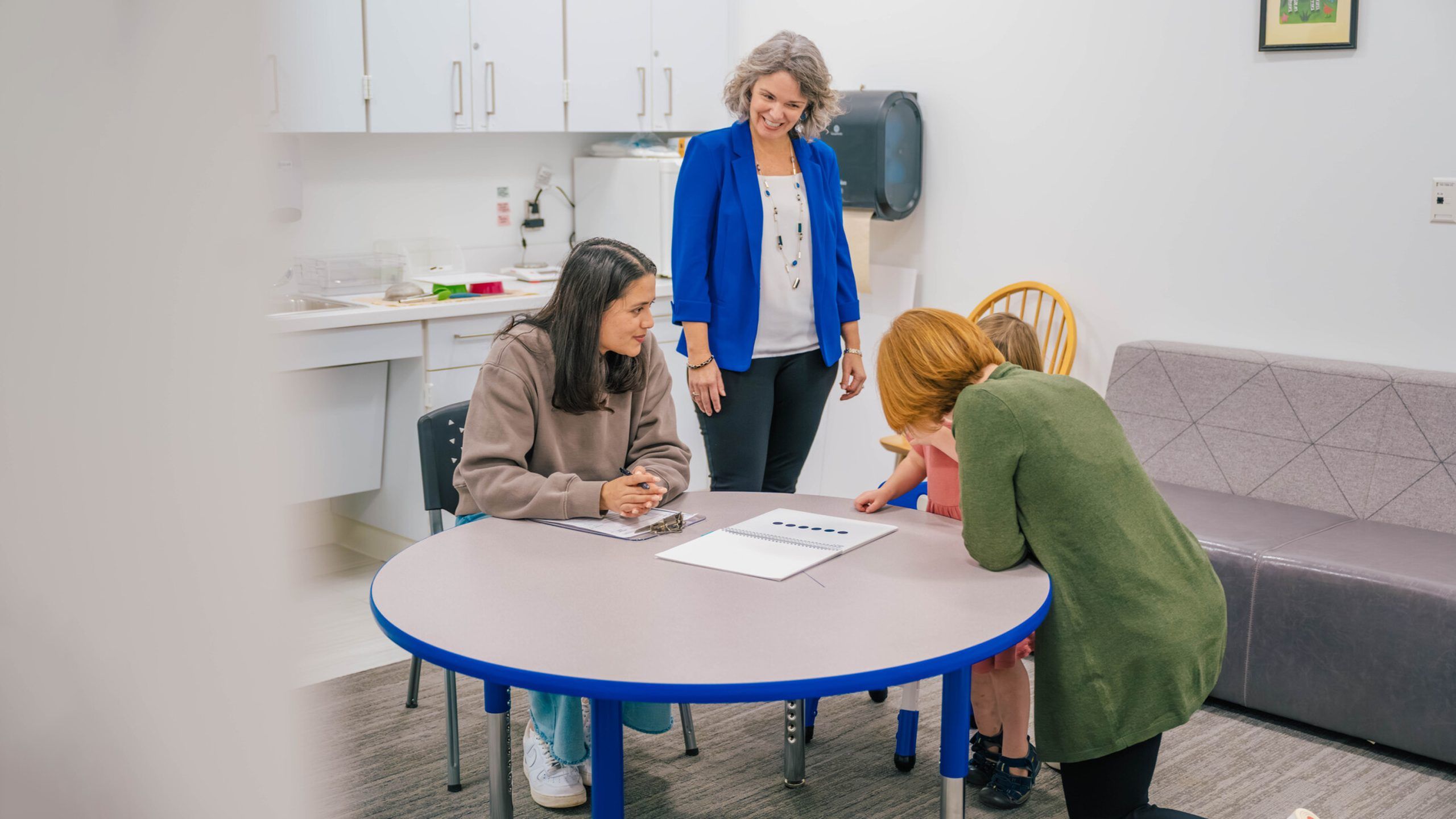

Photos: Wideman operates the Bod Pod, while Leerkes and grad student Shourya Negi work with a toddler.

Kids in control

Self-regulation is something we all do, often with very little thought about it. It’s what happens when we breathe deeply to relax when we’re angry and when a child is able to wait patiently for their turn to play with a toy.

“We think about self-regulation, at a high level, as a child’s ability to control how they feel and behave,” says Dollar, who is also part of UNCG’s Center for Women’s Health and Wellness.

“Their inner states, their behavior, their ability to cope with whatever is happening in their environment – a child’s ability to self-regulate is reflected by their ability to meet the challenges of the moment.”

The iGrowUP proposal is built on what scientists already know, that a child’s ability to self-regulate can predict obesity. Now the UNCG team wants to know if general self-regulation is enough for a child or if there are regulation skills that are specific to food.

Is choosing not to raid the junk food drawer within easy reach motivated by the same self-regulation skills as not stealing a toy from a sibling’s hands?

Photos: Dollar and Leerkes demonstrate iGrow lab methods.

Methodological Rigor

At ages three and five, child participants visit the lab in UNCG’s Stone Building and carry out various tasks. Each food-related task is paired with a non-food related task.

“We’ll code the children’s behavior,” says Leerkes. “How interested they seem to be, if they appear to get upset. We’ll code the strategies for how they cope. We’ll also measure their physiology, so we’ll have multiple levels of regulation.”

To get meaningful measurements on their levels of food and non-food regulation, Dollar says they made those tasks as similar as possible. If a child can’t reach a toy, it must be as challenging and similar in design as the task in which they can’t reach a piece of candy. That rules out whether the child’s frustration levels are skewed by another factor such as physical exertion.

“That’s a real strength of this study,” says Dollar. “We went to great lengths to design tasks across all the different types of regulation, and to make them parallel to one another.”

Parental empowerment

Photos: Leerkes, Shriver, Wideman, and their graduate students collect and process data in 2019 and 2024.

Since many of the children and parents who participated in iGrow will participate in iGrowUP, findings from the new study can be connected to findings from the original. For example, Shriver says, “With our iGrow data from earlier, we’ll be able to look at predictors of these self-regulation skills.”

The researchers have already observed links between stressors faced by new parents – such as lack of sleep and food insecurity – and their feeding practices.

An exhausted parent suffering from poor sleep, for example, was more likely to use food to soothe their baby when they became upset. A parent for whom food insecurity was a reality might urge an infant to continue feeding after they were full, out of concern for food waste.

They also saw it was possible for parents to temper their child’s feeding urges. Parents can be empowered with strategies to mindfully address their stressors and in turn reduce the chances that babies develop relationships with food that lead to overeating later in life.

They stress that their research will not be judgmental of parents. In fact, nuanced findings could help parents feel that they’re not being crammed into a “one-size-fits-all” model.

“There might be parents with a permissive feeding style that is generally considered a negative,” says Shriver. “But if that style is used with a child who has very good appetite regulation or general self-regulation, the obesity risk might still be low.”

Leerkes, Shriver, Wideman, and Dollar couldn’t be happier to conduct this study together. Dollar says, “We genuinely enjoy one another’s company. We work well together.”

“And having the opportunity to learn from each other has been really fun,” says Leerkes. “Most people would just come to it from one perspective. We’ve been able to integrate all of ours together.”